fno.org

|

|

| Vol 20|No 4|March 2011 | |

| Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or to anyone else you think might enjoy it. | ||

Laptop Thinking and WritingBy Jamie McKenzie, ©2011, all rights reserved.About author The secret to the powerful use of laptops for writing and thinking is an understanding of incubation, percolation, fermentation, reverie and idea processing. |

|

|

|

During the 1960s and 1970s, the teaching of writing in some schools went through a dramatic shift as the powerful ideas behind the Bay Area Writing Project — what came to be known in many places as "writing as process" — worked a quiet revolution in the way students developed and expressed their ideas.1 Writing as process should strongly shape the way students use a laptop to compose and express their ideas, but it is a rare teacher who has been granted the luxury of sustained, in depth exposure to this kind of writing — a rare teacher who has enjoyed a two week professional development growth experience like those offered by the Bay Area Writing Project.

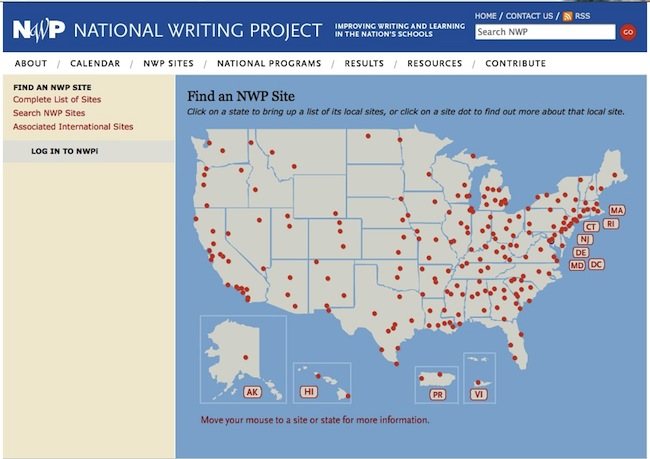

Sadly, many schools that are willing to invest in laptops are not willing to invest in the professional development that would engage teachers in actually using the kinds of writing strategies that would prove most useful when working with students on laptops are other electronic devices. I have asked many audiences in the past decade whether they have received in depth training in writing as process and very few hands are ever raised in the affirmative. This article will focus on a handful of important strategies that have their root in writing as process but are especially relevant to writing with digital tools. It will also point to resources that might be useful to schools setting up professional development sessions, but there is really no substitute for the kind of immersion offered by the Bay Area Writing Project and many of the programs offered by the The National Writing Project mentioned next. Note 1 - There are dozens of wonderful educators who contributed to this movement, and it is not my intent to list them all here, but most credit Janet Emig with the birth of the approach. In addition, we might point to the work of folks like Peter Elbow, Lucy Caulkins, Linda Flower, Joyce Armstrong Carroll and a host of others. The National Writing Project This group describes itself as "a network of 200 sites anchored at colleges and universities and serving teachers across disciplines and at all levels, early childhood through university. We provide professional development, develop resources, generate research, and act on knowledge to improve the teaching of writing and learning in schools and communities." http://www.nwp.org/ The map below shows their broad reach. A visit to their Web site offers up a host of resources as well as contacts with the 200 sites. Sadly, as this article is being written, this federally funded and successful program is being eliminated by President Obama and members of Congress intent on cutting budgets. (read update). It is hard to balance the rhetoric about "Race to the Top" with budget cuts that eliminate programs like NWP with proven results. If we hope to improve student writing across the USA or any other country, our governments must maintain support for professional development like that offered through organizations like NWP. The issue is worthy of letters from readers to members of Congress and the President.

Previous Articles on Writing with Computers To put this current article in context and to avoid repeating work published in previous FNO articles, I will present a brief annotated list here before moving into the new territory.

|

||

| The Tyranny of Roman Numerals

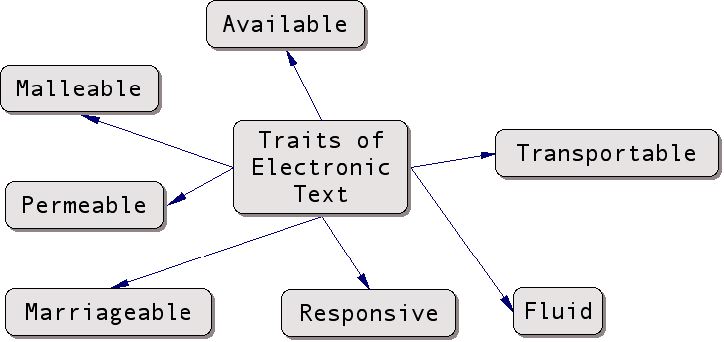

In the 1950s and the 1960s as well as in previous decades, many English teachers taught students like me to write using an outline as a first step to organize thoughts. In most cases, the outline relied upon Roman numerals to lay out the sequence of ideas. This step was supposed to occur before sentences and paragraphs might be drafted. Some teachers would require submission of the outline before allowing the writing of the first draft. This linear approach and outlining imposed some real restrictions on a young thinker and was in many cases premature. It did not allow for students to discover ideas in the process of composing ideas. Once the outline was submitted and approved, it was the student's job to translate the words and phrases of the outline into paragraphs, sentences and phrases full of meaning and shining with style. Roman numerals imposed a thought process that is somewhat rigid, almost tyrannical in its structure and formality — an approach at odds with a more creative and divergent thought process. Such outlining is still practiced in many schools and colleges as can be seen in this example from the Department of English at the College of DuPage. It is valuable for students to learn this approach, but it should be balanced with a sound introduction to concept mapping, cluster diagramming and mindmapping, so students learn to explore concepts, ideas and issues in a more creative and dynamic way. Imposing structures early in the exploration process can restrict the discovery of ideas. I recall an interview by a high school student in the mid 1990s who asked me questions for 30 minutes and then finished me by saying, "Thanks so much, Dr. McKenzie. You've been great, but I am afraid I can't use anything you told me." "Why is that?" I asked, perplexed. "Because I have a thesis — that librarians and libraries will no longer be necessary because of the Internet — and most of what you have told me undermined my thesis." A bit shocked by this comment, I asked her why she couldn't revise her original thesis, and she told me they were not allowed to change it. That's tyranny! Idea Processing One of the key features of process writing as introduced by the Bay Area Writing Project was its emphasis on pre-writing activities that were dynamic and expansive as well as divergent, avoiding any rush to premature speculation or ill-considered stances like the girl mentioned above. Under this approach, the framing of a thesis would come later in the writing process, assuming that the student does not start with sufficient understanding and expertise to frame a thesis that is tenable. Tenable?

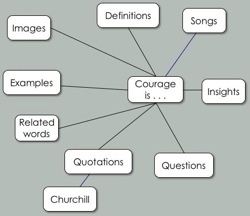

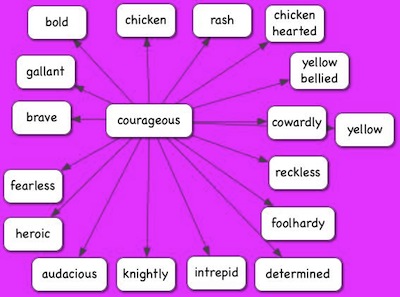

Access to the Internet with a laptop (or any computer), as that article demonstrates, can serve the students well as they Composing ideas in this case requires substantial work on definition. Before comparing the three lives, the students must develop a rich understanding of courage — one that is multi-faceted rather than simple.

"Courage is when someone faces up to danger without running." "Courage is when someone does something risky." Once they have looked more carefully, they may have 10-12 types of courage, including some types gathered from people like Winston Churchill. “Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.” The definitional exploration is a prelude for the research about the lives of the three people being compared. While the students may have heard of all three, it is unlikely they will know very much about them. And when they turn to Google, as most students will, they will find there are plenty of Web pages devoted to each:

In each case, the top or first listing is Wikipedia. With its intriguing blend of strengths and weaknesses as a source, Wikipedia is not much help to students looking for evidence of courage. In the case of Mandela, for example, the word courage only appears three times and none of these offers evidence. The word brave does not appear at all. Nor does bravery. Any evidence of courage must be inferred from actions Mandela took at various stages of his life, but there is nothing laid out for students to scoop up without much thought. The same is true of the Wikipedia articles for Joan of Arc and Captain Cook. Any evidence of courage must be inferred, with the one exception of Captain Cook's article, in which case there is a single use of the word courage accompanied by evidence:

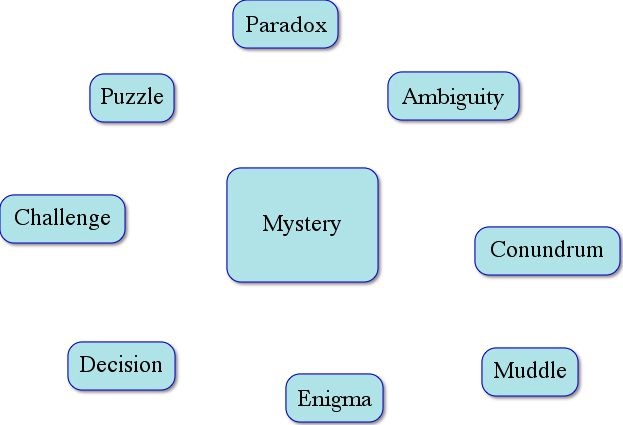

This ambiguity helps to demonstrate the limitations of Roman numeral outlining to capture and then build ideas. The students must gather dozens of stories about each person and then store them in a way that they might later synthesize what they have learned, deducing from their clues whether or not courage was displayed or required, and then they must struggle with the difficulty of comparing different types of courage, as if apples and oranges can easily or reliably be compared with each other. Grasping character is more of a mystery than a puzzle. It is like trying to grasp fog. There is not much to latch on to. It turns out that many of the most intriguing questions and issues in life are mysteries, and enigmas do not fit neatly into the patterned boxes of Roman numerals. Non-linear mind mapping is better suited to the exploration of mysteries, as students can search far and wide for clues and then collect them loosely at first. Later there will come a time for pondering, grouping and organizing. Building ideas is a bit like cooking a spaghetti sauce from scratch. You have to shop for the tomatoes, the spices, the onions, the mushrooms and the sausage, but the actual cooking requires washing, slicing, dicing, chopping, sautéing, seasoning, blending, timing, tasting, simmering, waiting and adjusting. But the metaphor fails to capture the idea of exploring a mystery since the desired outcome is quite clear from the beginning.

Gardening brings concepts like cultivation, seeding, fertilizing, weeding and harvesting into the picture. And if the students think about growing grapes from The Stages of Creative Production To win the chief benefits of working with electronic text and laptops for one's idea processing, students need to be aware of the powerful role of incubation in the development of ideas. Just as one ad stated, "No wine before its time!" the development of ideas often requires weeks and sometimes months rather than the mere day or two usually allotted to students in schools.

Since Wallas published his model, there have been many versions, alterations and modifications, but incubation remains an important stage in virtually all of these models. Some have inserted Frustration as a stage that usually confronts most thinkers. Since this stage almost always accompanies the incubation process, students must be forewarned and prepared for the struggle. If the student is unaware of the incubation stage and is permitted little time to mull over the challenge at hand, there is every danger that the resulting work will be superficial, hastily constructed and lacking perception and insight. Deep thinking requires a different kind of time. Even if aware of the incubation stage, is the student equipped to bring it on and nurture the fragile flame of creative thought easily snuffed out by the frustration mentioned above as well as various cultural pressures to respect conventional thought and draw (think) within the lines? In support of this creative process, Catford and Ray suggest that a creative thinker (or hero as they would call this person) must employ four main tools:

Path of the Everyday Hero: Sven Birkerts stresses the importance of deep time as a source of understanding and resonance:

Deep time? Take Otis Redding’s song, Sitting on the Dock of the Bay

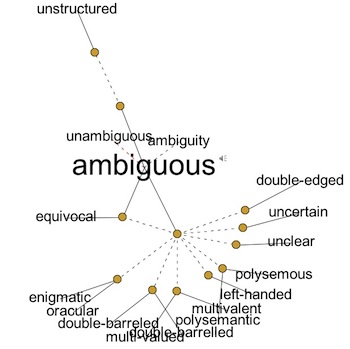

Stillness allows the mind to open and taste possibilities that may otherwise remain buried. When we rush about physically from spot to spot and task to task, when our thoughts dart from project to project, insights that dwell at deeper levels of consciousness rarely surface to win our attention. Ideas that are simmering may never materialize. Even worse, the simmering may not occur at all if the mind’s pilot light has not been activated. A fundamental message of this chapter is the importance of awareness. If the thinker knows about this kind of thinking, she or he can learn to kindle imaginative fires. Sadly, it is rare that schools will educate the young about incubation and reverie. Much of our most imaginative thinking will occur in dream states that are elusive. Although this process of kindling is nowhere near as reliable as turning on a radio or an iPad, with practice it is possible to nurture such states of mind and to make incubation flourish in the background throughout many hours of the day and night. Reverie Reverie is the dream state during which incubation, percolation and fermentation may take place. If we hope to see our students producing original, perceptive work, we must teach them the importance of reverie and help them to learn ways to slip into that frame of mind with some frequency and intention. We must help them to see the importance of reducing distractions and interruptions that will prevent them from finding that level of quietude and focus required to spawn deep thoughts. It is important to recognize that the culture does not always view reverie in a positive light, as a thesaurus may list quite a few negative terms related to the term:

And what, then, does all of this have to do with laptops? The fluidity of electronic text permits and nurtures idea development. Early thinking is easily modified and adjusted as nothing is written in concrete. Returning to the example mentioned earlier of students comparing the courage of Joan, James and Nelson, students begin with lots of collection — a task that is perfect for the laptop, since it supports browsing, harvesting and the storage of information related to the question. As evidence accumulates, the student is likely to begin formulating a position. Though many people think that writing is only that which happens when words are put on paper or into a computer, writing actually includes both the composing of ideas and the composing of sentences. One follows the other, but they often act in tandem or intermittently. The best way to employ laptops in support of powerful writing and thinking is to acquaint students with this notion that writing is about composing and that the laptop is a tool that supports both word play and idea "What am I going to say? Now that I know so much about these three people, how do I select one of them over the other two and then defend and substantiate my choice?" Synthesis of research findings is a very difficult thought process made especially problematic by the lack of scaffolding provided to most students that would make synthesis a part of their thinking toolkit. There are ways to equip all students with synthesis models like SCAMPER, but this is rarely done.

The purchase of laptops will not enhance student writing and thinking by itself. The potential to do so will only be realized if the school invests in program and professional development that equips both staff and students with synthesis skills like those outlined in "Building Good New Ideas." Additional Writing Resources Northern Nevada Writing Project — great resource with lessons incorporating six traits, writing lesson based on songs, mentor texts... National Writing Project |

||

|

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. |

||

Outline of chapters and description of book available here.

Order your copy of The Media Literacy Toolbox from the FNO Store

Imagine a student being asked which of the following three people showed the most courage in their lifetime: Joan of Arc, Captain James Cook or Nelson Mandela? How could they start an outline before devoting lost of attention to the main concept — courage? They might spend 5-10 hours just developing a deep and complex understanding of that idea, moving through a series of explorations as those described in the article, "

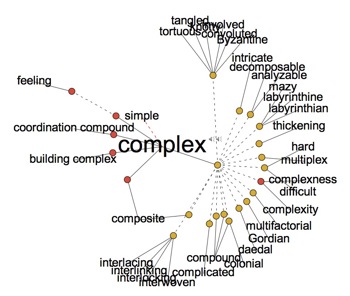

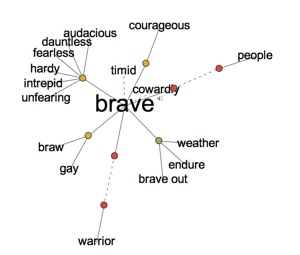

Imagine a student being asked which of the following three people showed the most courage in their lifetime: Joan of Arc, Captain James Cook or Nelson Mandela? How could they start an outline before devoting lost of attention to the main concept — courage? They might spend 5-10 hours just developing a deep and complex understanding of that idea, moving through a series of explorations as those described in the article, " wrestle with the concepts of bravery and courage, visiting online thesaurus sites, gathering quotations, reading poetry, watching videos and employing a mind-mapping program to collect and organize findings.

wrestle with the concepts of bravery and courage, visiting online thesaurus sites, gathering quotations, reading poetry, watching videos and employing a mind-mapping program to collect and organize findings. Prior to this exploration, many students may have just one or two types of courage in mind.

Prior to this exploration, many students may have just one or two types of courage in mind. Even though we might employ a jigsaw puzzle as a visual metaphor to grasp the idea processing challenge facing students in a writing task like this one, the evidence they must gather, while fragmentary, in the form of stories and examples, is also intangible, impalpable, and ambiguous. The pieces of a jigsaw puzzle are much more concrete and explicit. They also fit together neatly, unlike tales of human

Even though we might employ a jigsaw puzzle as a visual metaphor to grasp the idea processing challenge facing students in a writing task like this one, the evidence they must gather, while fragmentary, in the form of stories and examples, is also intangible, impalpable, and ambiguous. The pieces of a jigsaw puzzle are much more concrete and explicit. They also fit together neatly, unlike tales of human struggle.

struggle.

It turns out that students need to mix metaphors if they are to get their heads around this notion of original thought about mysteries. No single metaphor is sufficient, so we ask them to consider gardening, mining and carpentry as well as cooking as metaphors that add to understanding.

It turns out that students need to mix metaphors if they are to get their heads around this notion of original thought about mysteries. No single metaphor is sufficient, so we ask them to consider gardening, mining and carpentry as well as cooking as metaphors that add to understanding. which wine might be produced, gardening leads to crushing, fermentation and bottling.

which wine might be produced, gardening leads to crushing, fermentation and bottling.  Sittin’ in the mornin’ sun

Sittin’ in the mornin’ sun This thought process will often occur in the mind first, but such idea processing is actually an aspect of writing.

This thought process will often occur in the mind first, but such idea processing is actually an aspect of writing.  play, especially if it is loaded with software that supports this creative process. The use of mind mapping software is an essential element in realizing the full potential of a laptop to support effective writing. This kind of mindware radically enhances the synthesizing power of a thinker. Once the student has collected hundreds of stories about Nelson, Joan and James, the challenge of translating those findings into a stance is immense.

play, especially if it is loaded with software that supports this creative process. The use of mind mapping software is an essential element in realizing the full potential of a laptop to support effective writing. This kind of mindware radically enhances the synthesizing power of a thinker. Once the student has collected hundreds of stories about Nelson, Joan and James, the challenge of translating those findings into a stance is immense.