fno.org

|

|

| Vol 18|No 6|Summer 2009 | |

This article is based on Chapter Eleven of Jamie's new book, Beyond Cut-and-Paste, copies of which began shipping at the end of June. Order your copy. Table of Contents and sample chapters. Who was Joan of Arc? There is the Joan of Arc we read about in Wikipedia and the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Many of these articles turn Joan into an icon, a bit like Princess Diana. She has been Disneyfied — transformed into a caricature, as when the Hunchback of Notre Dame becomes cute and Pocahantas becomes a dazzling cover girl. Note images at http://www.meredith.edu/nativeam/pocahontas_4.jpg When we read Joan's letters, an image of her character emerges:

The tone of her letter to the English seems a bit imperious when you read the entire piece. If one did not note that she was illiterate and could not write, one might assume the words were hers and use them to substantiate a critical assessment. In fact, according to the translator, Allen Williamson, the letter was dictated to a cleric and Joan later denied having dictated certain portions and using the third person. The tone we note may have been the voice of the scribe, not the voice of Joan. It will remain a mystery, as with much of history.

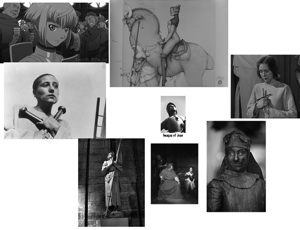

It is difficult to figure out who the real Joan was, even if we take the time to read the transcripts from her two trials and her correspondence. But it is even more difficult to find an image of Joan that stands up to scrutiny and might resemble the real Joan. As far as we can tell, there is no image available today that was created during her time by someone who actually saw her and painted her from life. Unfortunately, many of the images so freely available to students online may distort the person’s character in a number of ways, whether they be learning about Joan of Arc, George Washington or Matthew Flinders. In a cut-and-paste culture, students may be a bit too quick to capture an image of the person they are studying, snatching it up for a report without considering whether it is authentic.

http://jeanne-darc.dk/img_jeanne/onlyknowndrawing_big.jpg His Web site offers an extensive view of Joan of Arc images created over the past several centuries. The main index page for these images can be found at An especially vivid collection by one artist can be found at Taking images at face value In concert with the rest of this book, we would hope that students will learn to question the validity of historical images as a source of information about figures in history. We teach them not to take images at face value.

Instructions:

Depending on the age of the students involved, the teacher can either point them to specific pages or simply point them to the long, scrolling list of documents and challenge them to find pertinent testimony. In the transcript from “Saint Joan of Arc’s Trial of Nullification” located at http://www.stjoan-center.com/Trials/#nullification, they can read testimony that describes her appearance. The teacher sends them to the testimony of JEAN DE NOVELEMPORT, Knight, called Jean de Metz at http://www.stjoan-center.com/Trials/null04.html and asks them what they can learn from his words:

They rapidly learn that it is difficult to nail down the details of her appearance in a satisfying manner. Historians have been wrestling with these issues for years because the comments in the trials were mostly about her conduct and her religious principles. Stephen W. Richey devotes several pages to this challenge in his biography, Joan of Arc: The Warrior Saint (2003, Westport, Conn: Praeger.). He devotes Appendix C to a review of “Joan’s Personal Appearance.” He begins his attempt with the following admission: "There is not enough surviving evidence to give us any certainly as to what Joan looked like." Students can find Richey’s analysis by doing a Google search for the exact phrase “Joan’s Personal Appearance.” This will take them to his book and the Appendix C online. By engaging students in the search for evidence and following up with the testimony of an historian searching through the clues, the teacher gives them a firm grounding in the process of verification so they will always question the accuracy of images they find rather than taking them at face value. |

||

| Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles. |

||

When we turn to statues, posters and paintings, the task of verifying the portrayal is also quite challenging.

When we turn to statues, posters and paintings, the task of verifying the portrayal is also quite challenging.  According to the creator of

According to the creator of  An activity that works well to develop this questioning engages the students in collecting images about a figure from history like Joan from

An activity that works well to develop this questioning engages the students in collecting images about a figure from history like Joan from