fno.org

|

|

| Vol 20|No 2|November 2010 | |

| Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or to anyone else you think might enjoy it. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Addressing Tech A.D.D.:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As many schools rush to fill their classrooms with laptops and advanced technologies, there is growing evidence that the presence of these tools may sometimes prove distracting and may actually dilute the quality of learning. Recent studies have also documented the not surprising finding that these technologies along with social networking may also prove distracting at home. It turns out that Tech A.D.D. (Technology Attention Deficit Disorder) is a challenge that all schools, teachers and speakers should consider when planning learning experiences. Unfortunately, the zeal of some technology enthusiasts blinds them to these risks and silences discussion of this latest version of The Emperor's New Clothes.

In The New York Times on November 21, Matt Richtel reports in "Growing Up Digital, Wired for Distraction" that "Students have always faced distractions and time-wasters. But computers and cell phones, and the constant stream of stimuli they offer, pose a profound new challenge to focusing and learning." Richtel's article examines this challenge in some depth, using one student in California as a case study. While passionate about film-making, the student's school performance has dropped significantly. Richtel interviews a range of teachers at the school along with the principal in a way that spotlights a philosophical divide between those who see the distractions as a negative and those like the principal who argue that the school should adjust to the new desires of the students. One teacher is quoted as saying, “When rock ’n’ roll came about, we didn’t start using it in classrooms like we’re doing with technology.” The article raises important issues rarely addressed by technology lovers who are often quick to claim that today's students are "digital natives" who learn differently and need a different kind of school. They often mistake the glib and facile use of technologies for competence — as might be tested when a student makes use of a search engine, for example, and is capable of using Boolean Logic to narrow findings to the most relevant and reliable sources. The whole notion of digital natives is an unsubstantiated erroneous concept that lumps all of today's students into a glorified stereotype that conflicts with survey data reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation in Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year-Olds. While that report shows that the young spend many hours each day using various forms of digital entertainment, it also breaks out that usage to show that there are quite a few different patterns. Some spend most of their time gaming while others might concentrate on social networking. There are many variations in usage from student to student and age to age:

Several recent studies of home use of laptops by low income students have reported disappointing results in terms of academic performance at school. While several projects were launched with the hope that home ownership of laptops would prove academically beneficial, the opposite result emerged in these studies. "Computers at Home: Educational Hope vs. Teenage Reality" by Randall Stross in The New York Times, July 10, 2010, reports disappointing findings from three studies, one conducted with families in Romania, one with students in North Carolina and a third with students in Texas. As one researcher, Ofer Malamud, commented:

The Symptoms of Tech A.D.D. Wondering if you or someone you know is suffering from Tech A.D.D.? Have them take this quiz . . .

.Scoring:

Interpreting your score . . .

Capitulating to Popular Culture There are those who argue that schools must shift their activities and behaviors to meet the students on their own terms, but this represents a surrender to popular culture that conflicts with the deeper values of a well defined education. If we shift schools to embrace the entertainment so popular outside of school, we have joined forces with those identified in Chris Hedges' Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle as having diverted popular attention away from news and reality to entertainment and spectacle. It is a bit like substituting the Cliff Notes version of Hamlet for the real thing. Schools are intended to deepen and enrich the capacities of students to wrestle with challenging concepts, values and experiences. They are meant to instill a respect for the values and attitudes captured by models like Habits of Mind (Costa and Kallick):

When Matt Richtel reports in his article that many bright students at Woodside High do not finish reading assigned classics like Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle because they favor activities like Facebook, YouTube and making digital videos, it is evidence that the quality and depth of thought of such students has been weakened. When he describes teachers resorting to "read aloud" strategies because only a third of the students will read the assignments at home, it is more evidence of decline. The video interviews with five students accompanying Richtel's articles are vivid in their portrayal of the Technology Attention Deficit Disorder as four students describe their distractions, and one explains why he does not use such devices. A sixth video, "Fast Times at Woodside High," provides an overview of the issue, interviewing the principal as well as students. The video points out that the school "is struggling to find a balance between the thrill of immediate gratification and the rigor and discipline of traditional education." For some, these interviews and videos will be difficult to watch as part of the adult world seems helpless in the face of poor student performance and quick to embrace new technologies without critical judgment. The Times article does a good job of including teacher voices that sound an alarm rather than blow a trumpet. It is important reading for the staff of any school considering the implementation of laptop programs. When parents and schools fail to hold such students to high standards and make excuses for their poor performance, their acquiescence in the face of decline is lamentable, but even more serious is the attempt to justify such decline as some trendy new century learning style that goes along with TV shows letting viewers determine the fate of dancers rather than the judges. "Look how modern we are! Our students have learned to express important ideas in just a few monosyllabic words and characters. No need for paragraphs, logic or evidence. No need for figurative language or a carefully constructed persuasive essay. No need to read Vonnegut or Eliot or Dickinson. The Cliff Notes and YouTube will suffice nicely." When the school leader states in the video that such students will be fine because they will some day become great film-makers, we should shake our heads in dismay. Film-making is not the mere craft of splicing together images. What makes George Lucas a great filmmaker is a combination of craft with a deep and rich understanding of history, literature and society. When Lucas was a high school student his passion was drag car racing, and he wanted to be a professional race care driver. When an automobile accident changed his goals, he turned to film school. It was his reading of Joseph Campbell's The Hero With a Thousand Faces, first during college and later during the screen writing, that infused Star Wars with its deep mythical significance. Because students often change their dreams and their plans during adolescence, it is folly to support narrowly defined educational pathways that are dictated by the passions of the moment. The school is meant to provide a broadly defined education that provides students with ways of looking at the human experience to serve them well no matter where their vocational interests may turn. Who knows in advance how Vonnegut's Cat’s Cradle might influence the films, the inventions, the science or the sermons of students later in life? The idea is to give all students a taste of good literature because it speaks to the essential questions of life and should provide them with some understanding of such issues. Cat’s Cradle forces the reader to consider what happens when science is allowed to proceed unbridled and unchecked by any concern about its consequences. Is that book worth the time and attention of every high school student or do we buy into the notion that each student should be allowed to study whatever they wish?

A classroom or a lecture hall full of laptops, smart phones and other digital devices offers a heady mix of challenge and opportunity. Neither the benefits nor the problems are automatic. The devices definitely might enrich the learning of everyone in the room if they are used powerfully, but there is also a chance that they will dilute the quality of the learning. An algebra teacher planning to demonstrate a new concept and a new procedure will usually find eye contact and student attention to be crucial elements in the success of a lesson. If a third or more of the students are looking down at their screens instead of watching the instructor, there is a good chance that many of those students will not follow the presentation and will not grasp the new concept. When asked to replicate the procedure that they did not watch, they will be hard pressed to do so. They are effectively missing in action. Wise teachers know how and when to gain full attention. If something they are about to do for the class deserves full eye contact, they demand it (very nicely). Unfortunately, in some schools the 1-on-1 imperative is so strongly voiced that some teachers will be reluctant to ask students to give full attention or to close the lids of their laptops. After all, the argument might go, the students may want to take notes on the procedure being demonstrated. Keynote speakers face a daunting challenge when the room is filled with laptops and access to wireless allows roaming by members of the audience. Effective speakers seek a high percentage of eye contact and hope to create lots of chemistry, aspiring to keep the group on the edges of their seats through a dramatic presentation. At the same time, they may be laying out a fairly complex idea that requires focused attention. As the eye contact drops from the goal of 95% in a laptopless room to 35% in a laptopped room, the impact on learning may be severe. It should be noted that some keynote speakers have never risen above 35% eye contact even when the room is laptop free, in some cases because they simply have little dramatic capability and in other cases because they are reading from a prepared text without looking up. These are usually not very enjoyable learning experiences for anyone involved, and the attention of the audience is likely to wander for reasons that have nothing to do with the technology being used.

As they enjoy the results of this excursion, the speaker may encourage them to share their reactions with their seat-mates. Finally, after enough time has passed for them to absorb the fruits of the excursion, the speaker may ask the group to look up from their screens and join her or him for a few moments as a series of slides and important ideas are presented up front. The speaker works out a understanding with the group that makes the best of the Internet access without sacrificing the benefits of presentation. "Now turn to http://thinkexist.com and browse through the quotations on originality, synthesis or creativity and find at least one that stretches your thinking. Consider playing with parts of speech, since 'creative' will produce different results that 'creativity.'" This mixing of learning modes can work quite well, but the time devoted to excursions will probably reduce the important ideas shared by the speaker by some 50%. If the time allocated for the keynote is a mere 45 minutes, these excursions, delightful though they may be, can stand in the way of deep and rigorous learning. The approach works best when the group has 3-5 hours to explore important ideas together. The Play's the Thing Long before the advent of the laptop and all these digital devices, Shakespeare gave Prince Hamlet the following lines to speak:

Shakespeare was not writing about attention deficit disorder, but it occurred to me as I enjoyed an Intiman Theater production of The Scarlet Letter during the week I finished this article, that the rapt attention I noticed during this performance was a magical and very important human experience — something to be sought rather than squandered. The performance was riveting — not because there was a great deal of dramatic action, but because there was intense emotion and clever dialogue. Except for a few nappers whose lunch made attention impossible, I saw 100% eye contact. We have been enjoying story telling, drama and dramatic speakers for centuries. Thanks to new and recent technologies like YouTube and iTunes, we can enjoy many of these same performances without leaving our homes or venturing to a theater, but interruptions and distractions are an issue whether we are sitting at home or sitting in a theater. When I purchase a favorite TV program such as Mad Men, I find the lack of advertisements almost astonishing, allowing the drama to proceed, the emotion to build, the impact to multiply. When I return to the network viewing experience, the long string of ads is all the more distressing once I have tasted the ad-free experience. The $2.95 cost of buying the hour long program (actually only 42-43 minutes) seems a small price to pay. Before the performance of The Scarlet Letter in the Intiman Theater, a voice reminded the audience to silence cell phones and announced that photography, texting and recording was not permitted during the performance. Each learning experience deserves careful thought about the value or consequences of permitting, encouraging or blocking the use of various devices. There are many times when they will enhance and augment learning. But there are other times when "mute" is the thing.

© 2010 J. McKenzie |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Outline of chapters and description of book available here.

Order your copy of The Media Literacy Toolbox from the FNO Store

The Challenge of Holding Attention

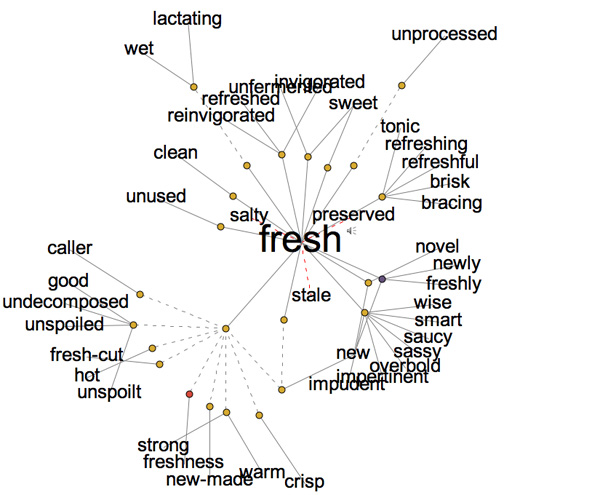

The Challenge of Holding Attention  One strategy that works well for keynotes in rooms full of laptops is to work out an understanding with the audience about different modes of learning that might occur during the presentation. The speaker intentionally suggests a series of learning excursions that relate to the topic of the speech but also identifies times when attention is desirable. Speaking on the challenge of promoting original thinking by all students, for example, the speaker may encourage everyone to look up the words "fresh" and "original" on the Visual Thesaurus.

One strategy that works well for keynotes in rooms full of laptops is to work out an understanding with the audience about different modes of learning that might occur during the presentation. The speaker intentionally suggests a series of learning excursions that relate to the topic of the speech but also identifies times when attention is desirable. Speaking on the challenge of promoting original thinking by all students, for example, the speaker may encourage everyone to look up the words "fresh" and "original" on the Visual Thesaurus.