fno.org

|

|

| Vol 20|No 4|March 2011 | |

| Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or to anyone else you think might enjoy it. | |||||||||||||

Knowtation:

By Alan Reid ©2011, all rights reserved. |

|

||||||||||||

| Jake is a 19 year-old college freshman. His American literature class is covering the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, but this writing does not exactly enthrall Jake. The final exam over The Great Gatsby is in two weeks, so Jake dedicates one hour each night to reading the novel. He unplugs himself from the rest of the world by turning off the television, the radio, the computer, and his cell phone. There is only one problem; by the time Jake finishes a chapter, he can’t remember what he just read. So he just keeps reading. Mrs. Anderson has assigned her 7th grade students a choice novel project. Each student selects a novel of interest, reads it, and gives a presentation at the end of the semester. On this particular day, the teacher asks her students to take out their choice novels for some quiet, individual reading time. Many of her students reach into their book bags, take out their e-readers, and turn them on. Kate is a college student with a car that needs an oil change. She walks into the auto shop and quickly sees at least nine people in the waiting area. The person at the desk informs her it will take about an hour and a half before her car is serviced. Kate sits down, pulls out her iPhone, and picks up where she left off reading her Jane Austen novel. Students of today are fundamentally different from past generations – not in terms of their cognitive ability, but in terms of accessibility to technological tools and the functions these tools can provide. The way in which educators must engage their learners is becoming increasingly challenging, but the foundations for becoming a better, more efficient reader remain the same. In fact, generative learning, or creating associations between prior knowledge and experiences with new, incoming information, increases reading comprehension and turns the reader into an active partner with the text. Jake’s problem with reading comprehension is not a new one. But, the manner in which Mrs. Anderson’s students and Kate encounter text is a modern phenomenon. In academia, because of the volume of texts and literature students are required to purchase and transport each semester, and because of their affordability ($100-$200), e-readers have become a viable, money (and lower back) saving option. In fact, “while we are already seeing the beginning of a shift to e-books on many campuses, higher education has probably up to five years to prepare for significant e-book adoption on campus – at least in the area of course materials, such as textbooks” (Nelson, 2008). Digital text may never replace hardbacks and paperbacks, but its compatibility with generative learning strategies makes it a useful tool for struggling readers and a convenient way to implement devices such as smartphones and iPods into the classroom instead of ignoring the powerful capabilities they possess. The term “e-reader” refers to a portable device, which at the most basic level is capable of reading digital texts and may or may not also contain other computing powers. Popular examples include the Kindle©, Sony Reader©, and the Barnes & Noble Nook©. The term mobile-reader refers to smaller devices such as the iPhone, iPod Touch, Android, and other smartphones, which allow the user to read digital documents through applications such as Stanza, Kobo, Iceberg, iBooks, and the Barnes & Noble Nook for iPhone. The Problem In 2010, 48% of graduating high school seniors did not meet the college readiness benchmark for Reading as indicated by the American College Testing (ACT) examination (ACT Profile Report - National: graduating class of 2010, 2010). As in the case of our college freshman, Jake, many students arrive on college campuses with the expectation they possess basic literacy skills, in which nearly half of them are deficient. College students often do not read actively for comprehension. Instead, college freshmen will use other ineffective strategies such as memorizing, re-reading, and skimming the text (Simpson & Nist, 1990). Thus, reading becomes an empty activity and inherently worthless. So, in order to promote literary understanding, and to save time, the reader should become an active participant by interacting with the text through the use of generative learning strategies, namely, annotation. What is knowtation? We’ve all done it. We’ve filled textbooks with notes in the margins. We’ve colored paperbacks with yellow and green highlighters. These are forms of annotation, and they are not a recent development. Mortimer Adler’s essay “How to mark a book,” first appeared in a magazine in 1940, and defines seven devices “for marking a book intelligently and fruitfully.” One of these methods is annotation: “Writing in the margin, or at the top or bottom of the page, for the sake of: recording questions (and perhaps answers) which a passage raised in your mind; reducing a complicated discussion to a simple statement; recording the sequence of major points right through the books” (Adler, 1942). Knowtation requires the learner to be an active reader and to synthesize textual information as he or she reads and connect this synthesis to personal views, experiences, and prior knowledge.

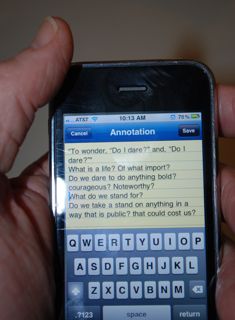

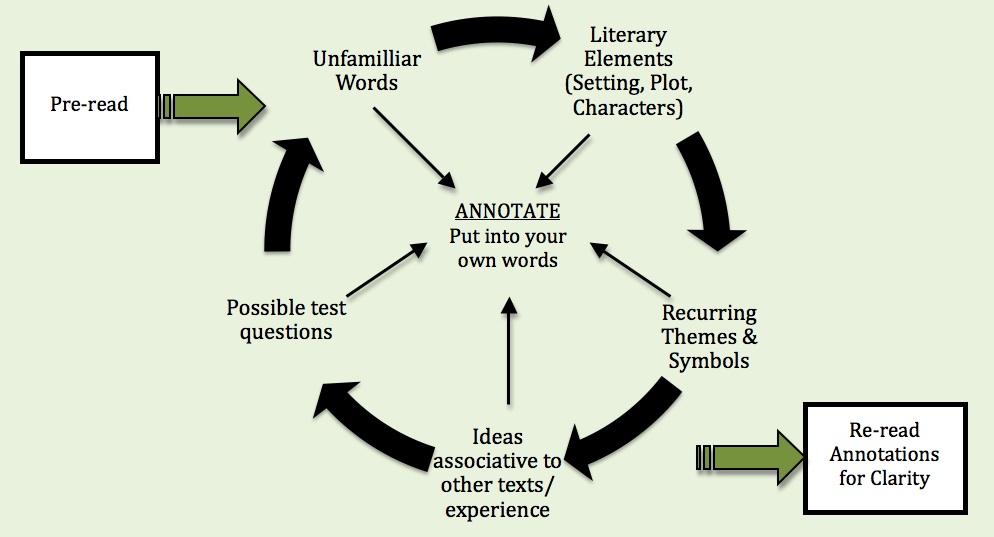

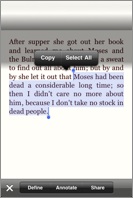

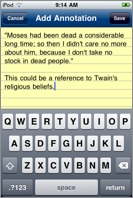

Figure 1: Model of annotation for comprehension in narrative text. Annotating a text is a useful strategy to initially engage the reader with the text and bridge the information in the text with prior knowledge and associations. According to Merlin C. Wittrock’s model of generative learning, “reading comprehension occurs when readers build relationships (1) between the text and their knowledge and experience, and (2) among the different parts of the text”(Linden & Wittrock, 1981). How to Annotate a Digital Text While digital texts are not an immediate threat to the paperback, they do lend themselves to easier annotation and navigability of the material. On a mobile-reader for instance, highlighting a text is as simple as the swipe of a finger, and the capability to take notes on the selected text is becoming more prevalent. Figure 2 illustrates a screenshot of highlighted text using the reading application Stanza. Once the material is selected, the reader has the option of making an annotation (Figure 3), defining the word (Figures 4&5), or sharing this selection with others through e-mail, Facebook, or Twitter (Figure 6).

Although these functions are cool, novel, and fun to play with, their foundation in generative learning theory is what helps promote their effectiveness and give digital texts an advantage over paperbacks. While there is no known research on the effect of annotations (as generated on e-readers and mobile-readers) on reading comprehension and student achievement, a multitude of research has been conducted on the impact of student-generated, paper and pen based annotations on test performance. Nist, Simpson, and Olejnik (1985) found that of “six major study variables (annotating/underlining, recitation, vocabulary, test planning, and lecture note format and content), annotating/underlining was more highly correlated with test performance among college students than any other variable” (Frazier, 1993). Heuristics for Educators Let students determine their preferred method of annotation. Annotation is an effective generative learning strategy, but not in isolation, and not for every student. Previous research also maintains that this strategy is only effective when instruction is provided on how to properly annotate. Simply telling the learner to annotate a text will not improve comprehension and understanding; in fact, identifying irrelevant material in the text may confuse the reader and divert his or her focus from important concepts (Bell & Limber, 2010; Rickards & August, 1975). In order for annotation to be an effective strategy, direct instructions on how to properly annotate should be provided first. References ACT Profile Report - National: graduating class of 2010. (2010). (p. 31). American College Testing. Retrieved from http://www.act.org/news/data.html |

|||||||||||||

|

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. |

|||||||||||||

Outline of chapters and description of book available here.

Order your copy of The Media Literacy Toolbox from the FNO Store