|

|

| Vol 12|No5|January|2003 | |

|

Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal, a parent, a colleague, a teacher librarian, a college professor, a poet, a magician, a vendor, an artist, a juggler, a student, a news reporter or anyone you think might enjoy it. Other transmissions and duplications not permitted. (See copyright statement below).

When students are challenged to explore truly demanding and intriguing questions, cluster diagramming software can prove a powerful ally to help map out all facets of the issue at hand. In the past decade we have devoted too much time to hardware and wires, and too little time to mindware and those learning strategies that might enhance student performance. While mind-mapping and cluster diagramming have been around much longer than laptops, the availability of user friendly software like Inspiration™ to support this kind of thinking is one the more promising developments to emerge from a decade of technology purchases. 1. Essential Questions Spawn Subsidiary Questions In the cluster diagram at the top of this page, students are trying to pick a captain worthy of their time, their loyalty and their trust.

Who shall it be? By organizing essential and subsidiary questions prior to conducting research, students will be able to focus subsequent energy on pertinent information instead of gathering huge piles of information, much of which will contribute very little to the choice of a captain. First the students must determine the traits of a good captain and surround the central question with those concepts. For example:

For each trait, the students must list subsidiary questions that would develop sufficient evidence to support making an informed judgment. Which captain had the most navigational skill? The students would have to find answers to questions like the following:

One quickly learns that digital resources are rarely sufficient to answer the kinds of questions posed above. It takes detailed stories of particular voyages to build the kind of evidence needed. Because such stories are seldom available in digital form, students must often turn to printed materials such as biographies and diaries when conducting any probing research. 2. The Old Research Ritual - Mrs. Smith’s Report Schools need to challenge students to focus on more than topical research like the state and foreign country reports we grew up with - topical research projects that still abound. These reports require little more than the gathering of basic facts. No need to build a case or prove a point. Topical research is mainly descriptive. If students study just one ship captain, they may read an encyclopedia article and just one biography to make a list of important facts about the captain's life:

A good biographer will have compiled this information from primary source materials and will have synthesized the findings into book format. All a student needs to do is collect, paraphrase and cite the source. Sadly, this kind of research does not equip students with the thinking skills listed by most states in their curriculum standards - the ability to analyze, interpret, infer and synthesize. When students research a single city, a single country or a single ship captain, they do little more than gather and collect. We can convert topical research into more profitable learning by requiring judgments and comparisons. We can also identify issues, conflicts or problems embedded in the topic.

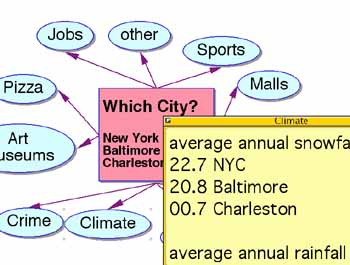

3. More Rewarding Search Strategies The old research put a premium on students collecting big piles of information almost as if big piles of information about a ship captain or a city might enhance understanding. We have all come to see that big piles can cloud understanding and obscure the truth we seek. Abundance can impoverish. When we change research to focus on essential questions, students learn to collect information that is pertinent and illuminating. Their search strategies become more sharply focused. They build searches that contain specifics and particulars. When comparing three cities such as New York, Baltimore and Charleston, for example, they may want to know the "average annual snowfall" and the "mean low January temperature."

Exact and particular search terms increase the chance of locating helpful information. The use of professional or scientific terms increases the chance of finding professional and more trustworthy information. If the student frames subsidiary questions with precise language and technical terms while mapping out the research, the search process is often more rewarding. In the advanced version of Google, for example, the student can conduct a search for the exact phrase "average annual snowfall," enter the name of the city and limit the search to domains ending in ".gov." At the top of the list is a page of snowfall statistics from NOAA - a bull's eye! (see results) New York's Central Park has averaged 22.7 inches of snowfall annually for the past 133 years. 4. Inspiration as a Note Taking Device Because the student has mapped out and categorized the important questions prior to collecting data, the subsequent findings can be stored where they belong back in the cluster diagram.

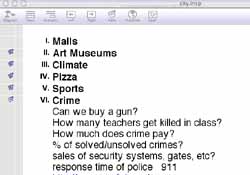

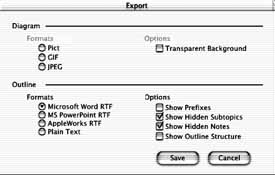

When students have mapped out what they need to know, they have also created a storage area that contributes to the building of understanding. Organizing findings - coherence - aids the construction process. In the diagram above, for example, the snowfall data is listed in a way that dramatically contrasts the three cities. If the student wants to avoid snow, the choice of city becomes clear. An actual choice, of course, would usually rest on a dozen or more comparisons across the criteria identified as critically important. 5. Developing Ideas with Mind Mapping In addition to storing data, mind maps may also provoke idea generation - the creation of insights distinct from those gathered during research. Because they offer visual displays, they facilitate flexible thinking. As facts, ideas and insights are collected, they can be manipulated and reviewed in juxtaposition almost like the twisting of a kaleidoscope. The collection of facts and concept fragments are somewhat like gems sparkling in trays. They cast light on each other. The process of developing new understandings with a mind map is somewhat like assembling the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle without having seen the picture on the puzzle box. Early efforts to place pieces together may not immediately show results, but eventually the central image begins to take shape. In the case of the mind map, early efforts help to define later ones. Unlike jigsaw puzzles, mind maps permit the invention or introduction of entirely new pieces or elements. Sometimes, the emerging outline suggests the hitherto unthinkable. Jigsaw puzzles are concrete, while mind maps are dynamic and organic. Thanks to programs like Inspiration™ a researcher may "toy" with ideas - move them about, test them, twirl them and turn them inside out alongside their opposites and their relatives. Looking for a solution to the many challenges facing the Snake River? The researcher may collect all the initiatives and plans that have ever been launched. The mind map is overflowing, but none of these past efforts have worked. The researcher must shake, rattle and roll the elements of all these initiatives until some new combination emerges with greater prospects. This synthesis process is described in some depth in the FNO articles, "Building Good New Ideas" and "Building Good New Ideas - Part Two." 6. Exporting from Inspiration The text students enter in the Outline view of Inspiration™ may be exported to a word processor such as AppleWorks or Word or to presentation software such as Powerpoint™. In either case, students will want select the Rich Text Format (RTF) format to fit the target program to which they wish to export text. Students may collapse outlines for presentations so that only the main ideas marked by roman numerals are exported. For the essay, on the other hand, it may make better sense to export most of the text. Resources Copies of Inspiration may be ordered at http://graphic.org |

|

Back to January Cover

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles. Unauthorized abridgements are illegal.

|

From Now On

From Now On