| As the information landscape shifts to offer far more information in an often befuddling manner that some have called "data smog," many schools are learning that traditional approaches to student research are inadequate to meet the essential learning goals set by most states or provincial governments. With hundreds of computers and dozens of classrooms connected to extensive electronic information resources, schools are recognizing the importance of reinventing the way they engage students in both questioning and research.

In order to support broad-based adoption of effective questioning and research strategies, a district team comprised of teachers, teacher librarians and administrators should conduct a search for an effective research model. This team may compare and contrast the features and traits of a half dozen models in order to settle upon one that matches district needs and preferences. In some cases, they may build their own model, synthesizing the best features of each model reviewed.

Once the district has identified a model that seems compatible and compelling, all teachers are provided substantial professional development support to learn the model's features as they relate to their own subject assignments. Such professional development should include substantial opportunities for the adult learners to employ the research model to explore an essential adult question drawn from their own life or their subject area. To develop a comfortable level of competence with such a model (given most teachers' limited prior experience with this kind of research) usually requires 12-30 hours of professional development time. This may be 2-5 days of summer workshop time.

A Choice of Models

There are several excellent reviews currently available for those who wish to begin such a search. One is by David Loertscher, Taxonomies of the School Library Media Program, 2nd Edition (Hi Willow Research & Publishing, 2000). Another summary and analysis is a chapter in a soon to be published Libraries Unlimited volume by Helen Thompson and Susan Henley,"Fostering Information Literacy: Connecting National Standards, Goals 2000 and the SCANS Report" that reviews the following models:

® The Big6 Skills Information Problem-Solving Approach to Information Skills Instruction,TM- Michael B. Eisenberg and Robert E. Berkowitz http://big6.com/

® INFOZONE, from the Assiniboine South School Division of Winnipeg, Canada http://www.assd.winnipeg.mb.ca/infozone/

® Pathways to Knowledge, Follett's Information Skills Model, by Marjorie Pappas and Ann Tepe http://www.pathwaysmodel.com

® The Organized Investigator (Circular Model) by David Loertscher, presented on the California Technology Assistance Project, Region VII's web site: http://ctap.fcoe.k12.ca.us/ctap/Info.Lit/infolit.html

® The Research Cycle, created by Jamie McKenzie. http://questioning.org

® Information Literacy: Dan's Generic Model - Dan Barron, University of South Carolina.

The purpose of this chapter is to present the Research Cycle in a concise and user friendly manner. Because such good work has already been done by those comparing and contrasting the other models, I will not duplicate their efforts here, other than to mention a special affinity with two of the models: INFOZONE and The Organized Investigator (Circular Model) because they offer much of the same emphasis upon questioning, exploration, synthesis and wondering that is intended by the Research Cycle.

Questioning First and Foremost

As will be shown in far more detail in subsequent chapters, when students explore truly demanding questions, they rarely know what they don't know when they first plan their investigations. They also tend to jump right into gathering without carefully mapping out the many questions they should be examining in their search for knowledge and understanding.

The Research Cycle differs from some models in its very strong focus upon essential questions and subsidiary questions early in the process. It also rejects topical research as being little more than information gathering unworthy of a student's time. Some other models are too easily converted into simple shopping trips. Students set out with a basket and enjoy an information binge, scooping up everything they can find about a state, a province, a foreign country, a famous person, a battle, a scientific issue or some item already conveniently available in containerized forms within some encyclopedia or book devoted to the subject. This kind of school research puts students in the role of information consumers and demands little thought, imagination or skill.

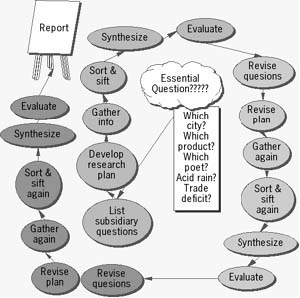

The Research Cycle puts students in the role of information producers. Like the two models mentioned earlier, INFOZONE and The Organized Investigator (Circular Model), The Research Cycle requires that students make up their own minds, create their own answers and show independence and judgment. Because students are actively revising and rethinking their research questions and plans throughout the process, they are forced to cycle back repeatedly through the stages listed below so that the more skill they develop, the less linear the process.

We teach teams of students to move repeatedly through each of the steps of the Research Cycle below:

- QUESTIONING

- PLANNING

- GATHERING

- SORTING & SIFTING

- SYNTHESIZING

- EVALUATING

Cluster diagrams created with Inspiration

Questioning

Unfortunately, much school research has been topical. Students were asked to “go find out about” Hitler or Connecticut or Adelaide. These assignments turned students into simple “word movers.”

New technologies make word moving - “cutting and pasting” - quite ridiculous. We should now emphasize research questions that require problem-solving or decision-making, questions that cause students to make up their own minds and fashion their own answers.

“How might we restore the salmon harvest?”

“In which Asian city should our family spend a 2 year visit?”

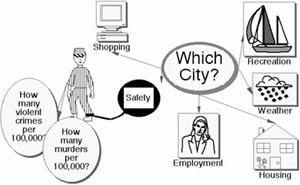

The first step in the Cycle is to clarify and “map out” the dimensions of the essential question being explored. The student or student team begins by brainstorming to form a cluster diagram of all related questions. These subsidiary questions will then guide subsequent research efforts.

A class of second graders working with a teacher might create the following list of questions on Inspiration™, for example:

Planning

Finding Pertinent and Reliable information

After the student team has mapped out the research to be conducted, the next step is to think strategically about the best ways to find pertinent and reliable information that will help them to construct answers to these subsidiary questions.

Students consider now where the best information might lie?

"Is it readily available in a book?"

"Can I find it on a CD-ROM?"

"Would it be available on one of our district's networked periodical collections like SIRS or Electric Library?"

"If I go to the Internet, where should I start? a search engine like Altavista? a directory like Yahoo? the source site itself like the Census or the Federal Bureau of Justice?"

Which of these sources are most likely to provide reliable information with the most efficiency?

Wise students ask for help with this stage, turning to the school or public librarian.

"Where is the best source for crime statistics?"

"Where can I find weather data?"

While the first rush to install networks seemed to circumvent the library and the librarian in some places, many people are beginning to recognize the continuing value of information mediation - the guidance provided by a skillful information specialist who knows where the best information resides and can point us to it with the least fuss, bother and wasted time. Many teachers, for example, have come to rely on the Web suggestions of librarian (now technology director) Kathy Schrock at http://discoveryschool.com/schrockguide/ Instead of wading through hundreds of sites to find a few good social studies or math sites, they trust Kathy to do that for them.

Even though students once rushed around and past the librarian on the way to the computer and the Internet, a few hundred hours of fruitless searching often seems to reduce student enthusiasm for random prospecting and surfing. Eager to get on with their project or inquiry, they turn to more reliable and well organized sources and they begin to welcome the "pointers" offered by a good librarian.

Thinking About Selection, Storage and Retrieval

In a time of information abundance (some would say "infoglut"), it is folly to jump into gathering without first giving careful thought to strategies for targeting and then storing the most relevant information. This early planning will greatly reduce the need for sorting and sifting later on. It will also contribute to the building of new ideas by emphasizing what information specialists call "signal" (information that illuminates) over "noise" (information that befuddles).

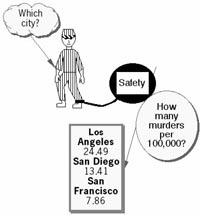

Studying a city like San Francisco in order to compare it with San Diego and LA and make a choice, they might find more than 2 million Web pages ("hits") using a search engine like Altavista.

Their first findings? A Chevy dealer, a hair stylist, a whole bunch of e-mail messages and a bunch of files that might cast little light on their search.

But they want to know if this city meets their criteria! Is it safe?

In many cases, students confuse "hits" on a search engine with progress toward insight and understanding. Since there was some tendency to reward length in times past and to confuse the quantity of information with the quality of the research, students may watch their accumulating mountain of "hits" with glee, not appreciating that they have been constructing the equivalent of an information landfill with any treasures concealed from view.

It doesn't help to gather 600 files about crime in San Francisco. What the student must do is ask telling questions such as "What is the homicide rate per hundred thousand and how has it been changing during the past decade?"

If they are asking telling questions, then they are only keeping the most important findings, and they are storing them where they belong.

If they use their cluster diagram for note-taking, they simply attach their findings as notes to the relevant part of the diagram. simply attach their findings as notes to the relevant part of the diagram.

A more challenging way to accomplish the same thing electronically is to set up a database file like the one outlined and explained in Chapter Thirteen. Once students have collected several hundred entries, they will find this system very helpful for sorting their findings by key concepts.

| Source: (Author, Title, Date, URL) |

.................... |

| Subject: |

.................... |

| Keywords: |

.................... |

| Abstract:

|

....................

....................

....................

....................

|

The goal of this step of planning for research is to create a storage system that will protect students from accumulating huge mountains of information in hundreds of poorly named files. Retrieval from such a "hodge podge" can be a daunting task.

We also hope to dissuade students from wholesale cutting and pasting. By planning ahead they will have an information storage system that will eventually support concept-based retrieval, synthesis, and analysis.

Organizing gathering around key ideas, categories and questions increases the likelihood that gathering will induce, provoke and inspire thought. Under older models, students gathered first and tended to think (if at all) later. We hope to maintain the tension of good questions, the cognitive dissonance and energy explored in Chapter Four - "Students in Resonance."

Gathering

If the planning has been thoughtful and productive, the team proceeds to satisfying information sites swiftly and efficiently, gathering only that information that is relevant and useful. Otherwise, teams might wander for many hours, scooping up hundreds of files that will later prove frustrating and valueless.

It is critically important that findings are structured as they are gathered. Putting this task off until later is very dangerous when coping with infoglut. It is also crucial that students only use the Internet when likely to provide the best information. In many cases, books, CD-ROMs and other networked information will prove more efficient and more useful.

Sorting and Sifting

The more complex the research question, the more important the sorting and sifting providing the data supporting the next stage - synthesis. Much selecting and sorting should occur place during the previous stage - gathering - but now the team moves toward even more systematic scanning and organizing of data to set aside and organize those nuggets most likely to contribute to insight. The team sorts and sifts the information much as a fishing boat must cull the harvest brought to the surface in a net.

Synthesizing

In a process akin to jigsaw puzzling, the students arrange and rearrange the information fragments until patterns and some kind of picture begin to emerge. Synthesis is fueled by the tension of a powerful research question. This stage is fully outlined in Chapter Four - "Students in Resonance" and again in Chapter Fourteen - "Regrouping Findings."

Evaluating

At this point, the team asks if more research is needed before proceeding to the reporting stage. In the case of complex and demanding research questions, students must usually complete several repetitions of the Cycle since they usually do not know what they don't know when they first plan their research. The timing of the reporting and sharing of insights is determined by the quality of the "information harvest" during this evaluation stage.

Reporting

As multimedia presentation software becomes readily available to our schools and our students, we are seeing movement toward persuasive presentations. The research team, charged with making a decision or creating a solution, reports its findings and its recommendations to an audience of decision-makers (simulated or real). Chapter Fifteen describes this process in considerable detail while warning against the glib and superficial, flashy multimedia reports that are becoming fashionable in all too many places.

|