Combating "Alternative Facts"

By Jamie McKenzie (about author)

I have argued for many years that the human question is the most powerful technology of all, and it is questioning that can most effectively reveal the hypocrisy and falsehoods lurking behind "Alternative Facts."

There is nothing new about "Alternative Facts" except for the name given to them recently by a White House spokesperson. Good social studies teachers have long felt it their duty to equip students with the thinking and questioning skills to tell the difference between fact and fiction, truth and falsehood.

Pharaohs, emperors, kings, queens, princes, princesses, popes, presidents and prime ministers have been twisting the truth to meet their needs for many centuries. Most of them even hired staff to spread their versions of the truth far and wide.

Is it getting worse?

Some commentators have suggested that the arrival of new technologies and social media have made "Alternative Facts" and the spreading of conspiracy theories more dangerous and more volatile, but their success and their popularity still depend greatly on citizens who are both susceptible and uncritical. Some on the Left choose to believe the "Alternative Facts" of extremist leftist commentators, while some on the Right choose to believe the "Alternative Facts" of extremist right wing commentators. In either case, suspension of critical thought is an unhealthy form of surrender undermining basic democratic norms.

Basic democratic norms? For many decades, political scientists argued that democracy cannot thrive unless the citizens and the politicians honor certain values and attitudes. When fledgling democracies floundered and suffered street violence and coups d'états, it was blamed on the citizens and leaders who failed to honor those norms. For democracy to flourish, citizens must, for example:

1. Be patient with compromise

2. Be tolerant of other points of view

3. Be willing to keep emotions from overwhelming logical thought

4. Honor laws governing public discourse and meetings

5. Accept that control of the government may swing back and forth between different leaders and parties

6. Reject violence and threats of violence as a way to settle matters

The above is a partial list, but you can find more examples at the NCSS Web site (National Council of the Social Studies) and in articles by mainstream political scientists like "Citizenship Norms and Political Participation in America: The Good News Is ... the Bad News Is Wrong" by Russell J. Dalton at the Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of California.

Teachers are expected to develop the critical thinking skills of their students so they will view the claims, charges and counter-charges of politicians, world leaders and their proponents with skepticism. Even when so equipped, of course, they may choose to lay logic aside and enjoy the emotions that thrive when fully and then blindly committed to a cause. Sometimes called "The wisdom of the crowd," such immersion in a cause can all too often result in mob violence and atrocities.

Examples from History

Looking back at Henry VIII of England, this king often encouraged "Alternative Facts" when it came to wives who had disappointed him — a habit that cost some of them their heads. He was also prone to rely on rumors and gossip as a basis for beheading court figures he suspected of disloyalty. He found the judges in his courts quite cooperative and eager to produce the "Alternative Facts" he desired. At times they convinced witnesses to provide these stories by forcing false confessions by means of torture.

It would be difficult to find a political leader who has not twisted truth in some way. Sometimes it is a simple matter of projecting confidence in a good future when things are going poorly. Often it is campaign promises that were always "pie in the sky" or "pipe dreams."

It is important to note that some forms of misinformation are more serious than others, as when a Hitler blames Jews, Gypsies and Communists for all the problems facing pure-blooded, Aryan German citizens — "Alternative Facts" that led to millions of deaths and atrocities that boggle the mind and should trouble the soul. Targeting groups in this way while encouraging mass hatred and fear of them is fundamentally undemocratic but often sadly effective.

When we hear a candidate appealing to fears, emotions and rage, an alarm should go off. Classic examples of demagogues would include Mussolini and Hitler. Some would add the American - Huey Long - to the list. All of these specialized in "Alternative Facts" and sometimes added stirring music to energize followers and win their unquestioning loyalty.

The demagogue is often charismatic and appealing to some citizens, while repulsive, crude and offensive to others. He or she thrives (and plays) upon the discontent and alienation of the downtrodden, the disaffected and the alienated — those who have pretty much given up on the political system and have decided that normal politics are corrupt and hopeless. They are so tired and disillusioned, they are willing to embrace whatever fantasy suggests a way out of their misery. They are quick to throw both caution and logic to the winds.

They have little patience with critical thinking and worry little about facts and evidence.

"Don't bother me with the facts, Son!"

In classic political science, the demagogue is said to "mobilize the masses." By this the political scientists mean that a demagogue will wake up, energize and enlist those who have been sleeping and disengaged, those who are especially vulnerable to emotional appeals.

Mentalsoftness

If schools fail to meet the challenge of teaching critical thinking, many people grow up prone to mentalsoftness and become easy recruits for those who specialize in demagoguery. At the same time, even when such skills are taught, there is no guarantee they will be practiced later in life.

Mentalsoftness

1. Fondness for clichés and clichéd thinking - simple statements that are time worn, familiar and likely to carry surface appeal.

|

|

2. Reliance upon maxims - truisms, platitudes, banalities and hackneyed sayings - to handle demanding, complex situations requiring thought and careful consideration.

|

|

3. Appetite for bromides - the quick fix, the easy answer, the sugar coated pill, the great escape, the short cut, the template, the cheat sheet.

|

|

4. Preference for platitudes - near truths, slogans, jingles, catch phrases and buzzwords.

|

|

5. Vulnerability to propaganda, demagoguery and mass movements based on appeals to emotions, fears and prejudice.

|

|

6. Impatience with thorough and dispassionate analysis.

|

|

7. Eagerness to join some crowd or mob or other - wear, do and think what is fashionable, cool, hip, fab, or the opposite or whatever . . .

|

|

8. Hunger for vivid and dramatic packaging.

|

|

9. Fascination with the story, the play, the drama, the show, the episode and the epic rather than the idea, the question, the argument, the premise, the logic or the substance. We're not talking good stories or song lines here. We're talking pulp fiction.

|

10. Enchantment with cults, personalities, celebrities, chat, gossip, hype, speculation, buzz and blather.

The term MentalSoftness is a term coined by Jamie McKenzie in May, 2000. (See FNO, May, 2000, "Beyond Information Power.").

|

Classroom Tactics and Learning Activities

There is no quick fix. Determining what is true and what is false takes some digging as well as a habit of mind once described by Neil Postman as "crap-detecting. In his 1969 article, he credits Ernest Hemingway with the invention of the term:

It may be worth saying that the phrase, “crap-detecting,” originated with Ernest Hemingway who when asked if there were one quality needed, above all others, to be a good writer, replied, “Yes, a built-in, shock-proof, crap detector.”

In this article we will consider a number of ways teachers might cultivate the habits of mind required to approach statements, theories and "Alternative Facts" with healthy skepticism. Some will prove more effective than others, and changes in the way people now learn about their world should cause social studies teachers and media studies teachers to revise their approaches to this challenge.

It should be stated from the outset that logical analysis is not always sufficient when it comes to evaluating politicians and their claims. There are times when cynicism trumps logic, as we witnessed in the American 2016 presidential campaign. Both candidates had very high disapproval ratings and were deemed untrustworthy by huge numbers of voters. In a political system strongly influenced by big money and special interests -- influence that mostly occurs off camera -- there are many unknowns. Without transparency (the ability to see what is really going on), suspicions and doubts fester.

1. Blame Games

Make sure your students know about blame games of the past and how they led to mob violence and tragedy. Hopefully, these horrors will serve as cautionary tales that will influence their own future behaviors in a positive manner.

Over the centuries, political leaders, pundits and writers have blamed groups or individuals for whatever troubles are plaguing the citizens. Before the revolutions in the American colonies, France and Russia, economic problems could be blamed on King George, Louis XVI and Tsar Nicholas II. At other times, difficulties of all kinds have been laid at the feet of unpopular groups such as Jews, Gypsies, Protestants, Catholics, Hindus and Muslims. Sometimes the blame is used by one sect (Sunni) against another (Shia.) In the USA, hard times have been blamed from time to time on waves of immigrants like the Italians, the Irish, the Greeks, the Germans, the Poles, the Somalis and the Russians.

In 1891, eleven Italians were lynched in New Orleans when a trial failed to convict them of murdering the chief of police. The mayor at the time was quoted as saying, ". . . the worst classes of Europe: Southern Italians and Sicilians . . . the most idle, vicious, and worthless people among us." He claimed they were "filthy in their persons and homes" and blamed them for the spread of disease, concluding that they were "without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion, or any quality that goes to make a good citizen." Source: Liles, Stinson (May 9, 2017). "Rhetoric Becomes Gruesome Reality on a Sunny Saturday Morning in 19th-Century New Orleans". Southern Hollows: A Podcast of Erstwhile Unpleasantness.

If students watch the 1999 HBO movie Vendetta, starring Christopher Walken, they will note how an American community can scapegoat an entire ethnic group of newcomers for many of the ills they face, especially when leaders like Mayor Shakespeare fan the fires of hatred and promote the worst kinds of stereotyping.

There are, sadly, too many similar stories of American mob violence against groups. The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 saw working-class whites killing, maiming and hanging blacks they blamed for being drafted into what they called at the time, "The nigger's war."

In 1921 mobs rampaged through the black neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma, killing hundreds of people and destroying most of the homes. Not all textbooks or teachers have paid attention to these dark episodes that illustrate how quickly stereotyping and scapegoating can lead to violence. It is as if some people believe such events will never happen again as long as we pretend they never happened in the first place.

When teachers involve students in studying the way these horrific "blame games" have operated in the past, perhaps they will have a basis for understanding any similar games being played during their own times.

When someone casts blame, they are advancing a theory of cause and effect. In many cases, it can neither be proven or disproven. Often the blame is tied to a conspiracy theory that suggests the dirty work is being done in secret. Because it is done in secret, the argument continues, one cannot gather evidence and bring the scoundrels to justice in normal ways.

"You'll just have to take my word for it! Trust me!"

Hearing these claims and these arguments, some citizens like those in New Orleans back in 1891 will feel they must take justice into their own hands. When the court refused to convict the 19 Italians, the mob was quick to substitute "Alternative Facts" and a different verdict.

2. Truth or Consequences

Students must come to see that "truth matters." While it may be fashionable at times for commentators to laugh it off and pretend it is an old-fashioned concept no longer suited to a "post truth world," there are dozens of times in the personal lives of students when they will swiftly agree that "truth matters."

This is a good time to ask students to make a list as a homework assignment. As teacher, you can give them a few examples like the following and ask them to come up with 5-10 more overnight.

• Buying a used car. Is the odometer telling the truth?

• A friend wants to borrow $500 and says he will pay it back within 7 days.

• A new boyfriend/girlfriend says they will see and kiss no one else.

• A teacher says you have great potential for college.

• A coach says you are wasting your time and should try a different sport.

Once they have made their lists, ask them to identify the consequences that result in each case when someone betrays them and lies. There is no guarantee that this exercise will create a respect for honesty that will transfer over into the political domain, but explicit discussion of truth can be thought of as a worthwhile building block.

3. Expertise

In recent years, many people have become suspicious of experts and less inclined to trust their advice and opinions. One of the time-honored methods to assess the validity of an article or an essay was to ask questions about the author's training and credentials, but such steps seem to have less value these days as the information-gathering habits of citizens have moved dramatically away from such articles in magazines and newspapers.

In an age of punditry when so-called experts sit on TV and speculate, it may not matter much what university the pundit attended or what rank he or she reached in the armed services. Speculation is not so much about facts as it is about opinion. Television and cable have both moved dramatically away from what used to be called "news." Those who sit on panels providing commentary are not required or expected to bolster their opinions with facts.

Even in the past, while inquiries about credentials might have seemed a sound method to judge veracity, three well-trained historians with excellent credentials could often come up with quite different biographies of the same person or explain historical events in wildly different ways, bringing to their writing points of view that influenced their storytelling and resulted in "Alternative Facts."

Given the way most people are now learning about politics and current events, training students to consider the credentials of authors seems less useful than it used to be.

The majority of citizens in the USA now view world and national events through media outlets that rely upon pundits - some of whom have impressive credentials and some of whom do not. In some cases, TV "journalists" may not have much experience or background in journalism and are more "news reader" than reporter.

In January of 2016, according to a survey of 3,760 U.S. adults by The Pew Research Center, 24% said the most helpful source to learn about the election was cable news, 14% said social media and 14% said local TV. 13% named news Web sites, 11% radio and 10% network nightly news. Only 3% cited local papers - the same per cent as comedy shows - and 2% cited national newspapers. In a related 2014 study Pew found that Americans tend to select news sources that match their own politics:

When it comes to getting news about politics and government, liberals and conservatives inhabit different worlds. There is little overlap in the news sources they turn to and trust. Source: "Political Polarization & Media Habits"

It is as if many Americans have decided to gather their news where they are comfortable with the sentiments and bias of the commentators, suspending judgment about their expertise as well as the facts these commentators may or may not have considered while forming their opinions. In some circles, the news reporting of outlets conflicting with one's own point of view may be dismissed as "fake news." And then there are stories that go viral on the Internet that are completely false, like those posted on Facebook during the 2016 election by Russians using fake accounts.

This approach to learning about the world has been called "ego-casting" by Christine Rosen writing in The New Atlantis. Rosen says we seek sources that will reinforce and support our beliefs at the same time new media are eager to keep serving us what makes us comfortable.

Eli Pariser has called this phenomenon "The Filter Bubble" as Google modifies our findings to align with previous searches and preferences. Rosen says this is a form of intellectual starvation, but it is one freely chosen, albeit often unconsciously.

Even though information-gathering habits are changing, teachers should still engage students in questioning the veracity and the expertise of authors and Web sites so they will see that misinformation is widespread.

Kathy Schrock has provided an impressive array of critical thinking tools, instruments and activities here along with a list of bogus sites that can be useful in heightening students' awareness and concern about fake information. As for her expertise, "Kathy Schrock has been a school district Director of Technology, an instructional technology specialist, and a middle school, academic, museum, and public library librarian. She is currently an online adjunct graduate-level professor for Wilkes University (PA) and an independent educational technologist." More about Kathy.

4. Triangulation

Given the dramatic shift in the information landscape and the way most people are learning about their world, triangulation may be one of the more trustworthy strategies we may teach our students to assess the veracity of claims, theories and reports they will encounter.

Instead of digging deeply into the theory, the story or the report itself, one seeks at least three sources that are repeating it as if were true. These three sources should be quite divergent, drawn from sites or news outlets that represent quite different points of views and biases. One might see if Fox News, CNN and MSNBC are all reporting the same story, for example. One might also wait at least 24 hours to see if the story endures.

Students will learn that news outlets are under pressure to break stories early – pressure that sometimes means that stories surface before their truthfulness has been carefully tested. Tonight's headline sometimes becomes tomorrow's retraction. They may also learn that pressures to win ratings will sometimes push the news media to share sensational stories and scandals before they have had a chance to verify all of the facts. These are pressures that influence reporting across the entire political spectrum, and those who approach such stories may sacrifice audience share if they take the time to perform "due diligence."

During the course of a month, a class can monitor a dozen or more breaking news stories in this fashion to see how many survive for more than 48 hours and how they are reported across the political spectrum.

5. Weighing the evidence and the logic

Another time-honored approach of good social studies teachers is to show students how ideas must be supported by both evidence and logic to deserve serious consideration.

In one of the world's most impressive curriculum documents, New Zealand has made a strong appeal for schools to develop a generation of thinkers who are capable of making up their own minds:

"Students who are competent thinkers and problem-solvers actively seek, use, and create knowledge. They reflect on their own learning, draw on personal knowledge and intuitions, ask questions, and challenge the basis of assumptions and perceptions." Source

In a 2008 article, "Challenging Assumptions," I covered this challenge in considerable detail, parts of which are included below.

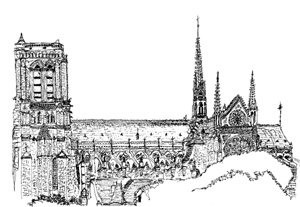

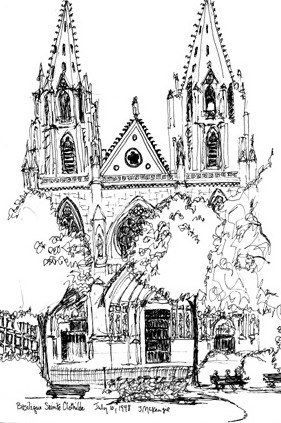

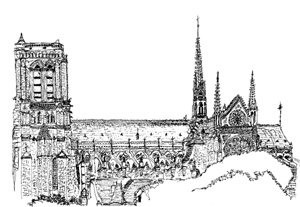

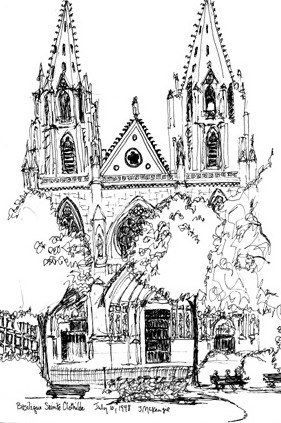

Picturing an Idea

Few people stop to consider what may or may not lie below the surface of an idea or proposal. In working with students, it helps to provide them with visual images of ideas along with their supporting structures. A well formed idea is a bit like an iceberg or a building. There should be plenty of logic, supporting evidence and careful thought below the surface. The idea itself may appear as a simple sentence or two but its value depends upon its foundations much like a cathedral or a sky scraper.

Continuing with the building metaphor, students are encouraged to think of themselves as building inspectors. When buying a house, smart consumers pay for a housing inspection to check all parts of the house before making a final decision.

|