Order McKenzie books online with a credit card

Bring Jamie to your school or district for a great workshop.

November Issue

Vol 27|No 2|November 2016

A good question, |

|---|

If we hope to see students engaged in research that matters, we must avoid time-honored rituals that require little more than gathering, scooping and smushing. Topical research has long served to limit the value of student exploration, as "go find out about" requires very little more than the collection of heaps of information. Especially with the electronic shovels that arrived a few decades back with the Internet, hunting and gathering has been simplified and expedited so radically that little thinking or labor is involved. Students can copy and paste at will, which has led to widespread plagiarism rather than authentic learning.

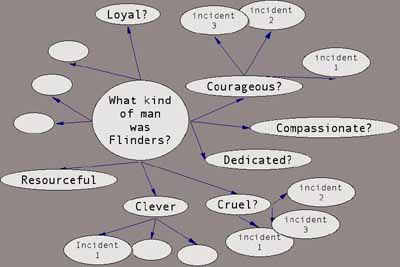

A good question should inspire and drive the research A focus on essential questions or questions of import will set students free from the tedium and triviality of topical research. Instead of "finding out" about Benedict Arnold, Margaret Thatcher, Matthew Flinders or Joan of Arc, the student might explore questions like the following:

Teachers should introduce their students to both types of questions — essential questions and questions of import — encouraging them to identify promising issues and questions from the curriculum content being studied. If a class has never done this kind of research and questioning previously, it would be wise for the teacher to lead the group through a shared experience, scaffolding the skills required for success. In this case, the teacher will suggest the question that will inspire the investigation. Ultimately, the goal is to challenge students to formulate their own meaningful questions. photo of Matthew Flinders © J. McKenzie Good questions may produce good ideas We expect all students to make up their minds and create ideas. Research should not be about copying the ideas of others. They can assess the character of Benedict Arnold, Margaret Thatcher, Matthew Flinders or Joan of Arc by looking at their actions and reflecting upon what those actions signify, just as they would when doing character analysis with someone from a novel. What kind of man was Captain Matthew Flinders?

We expect students to use primary source materials to gather evidence that will enable them to build a case. The source of stories and incidents might be a document located at Project Gutenberg's site - a collection of historical documents such as A Voyage to Terra Australis, by Matthew Flinders. Or they may browse through the Flinders Papers at the UK National Maritime Museum.

There are many experts who have disagreed about Flinders. Even though he is deservedly treated as a hero by many Australians, as with many heroes, he had feet of clay. Students must look past the claims and assertions of historians and come to their own conclusions based on his actions. During the 1980s and 1990s, constructivist learning theories were quite popular in the USA. These theories promoted the value of students building their own ideas and meanings. With the advent of No Child Left Behind and high stakes testing, such progressive learning strategies fell out of favor. If students cannot build their own ideas and challenge the ideas of others, they become prey to marketeers, propagandists, demagogues, snake salespersons and false prophets. They become susceptible.

In Orwell's 1984, the government tried to eliminate independent thinking. It was called "crimethink" and the government hoped to eliminate such thinking by restricting the general population to a vocabulary of fewer than 1,000 words. The health and well-being of any democracy depends upon a well-informed citizenry capable of wrestling with difficult concepts. If citizens cannot think for themselves, they are easily mobilized and manipulated by unscrupulous leaders and demagogues. And after the research and thinking, a Great Report We expect students to share their thinking and their findings persuasively and effectively. Conducting the research can be a bit like a safari, a hot air balloon ride or a roller coaster ride. Actually, since the student should be driving, bumper cars, race cars, plows and augurs might make better metaphors. There should be plenty of driving, digging, wondering and discovering. The research process should be exhilarating. The student repeatedly tastes the joy of AHA. Composing and then presenting the report should also be thrilling, as the student is hoping to communicate the excitement felt during the research and share dramatic findings with pizazz and panache. Standing in front of an audience, the student shares findings that bedazzle and delight everyone listening and watching. It is up to the teacher and class to agree upon the criteria and standards for the evaluation of presentations. There may be several different rubrics, each of which will focus on one aspect of the presentation. Just one is provided below as an example.

We hope to avoid PowerPointlessness and what Dilbert calls “PowerPoint poisoning.”9 Too many bullets. Too much crummy clip art. Simple thoughts. One liners. Mind bytes. Mind candy. Death by powerpointing! Multimedia presentations should be compelling and persuasive. Note: You will find extensive resources supporting this kind of research in The Great Report, an outline of which may be found here. Written materials, art work and photography on this site are copyrighted by Jamie McKenzie and other writers, artists and photographers. Written materials on these pages may be distributed and duplicated if unchanged in format and content in hard copy only by school districts and universities provided there is no charge to the recipient. They may also be e-mailed from person to person. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted. FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles. From Now On is published by FNO Press mckenzie@fno.org 935 Lincoln Pl 935 Lincoln Pl Inquiries via email please

|

||||||||||