Important Ed Tech Book Reviews

Just in Time Technology

|

|

| Vol 10|No 8|May|2001 | |

|

Please feel free to e-mail this article to a friend, a principal,

How is searching for the truth different

How do we discover truth in the world around us? How do we teach students to discover their own truth or truths about the most important questions and decisions in life?

Answering any of these questions requires more than the mere collecting of facts. As Sven Birkerts wrote in his Gutenberg Elegies . . .

Schools often stop short of showing students how to fashion what Birkerts calls "import." The collection of facts without much purpose is trivial pursuit. (See FNO, February, 2001, "From Trivial Pursuit to Essential Questions." http://fno.org/feb01/covfeb.html ) We should be teaching students how to move past collection and gathering to insight, understanding and the discovery of import. We should be showing them how to discover "the heart of the matter." Schooling should be a matter of discovering "lux et veritas" -Yale University's motto ("light and truth.") The motto "lux et veritas" is taken from Psalm 43:3 "Send out your light and your truth, let these be my guide." Young people do not become wiser simply by amassing huge mountains of data, as we can see when we look at the challenge of studying any city. What kind of city is New York? is Sydney? When we read about a city in an encyclopedia article, are we coming to understand the true New York? the true Seattle? the true Sydney? the true Melbourne or Adelaide? Try reading about a city that you know well (click here http://dir.yahoo.com/Reference/Encyclopedia/).Do you recognize the city you know in the article you read? What is missing? What kinds of information are left out? If I asked you to supply three words that would best describe the character of a favorite city, what words would you use? Do any of these words appear in the encyclopedia article? I asked two friends what words they would apply to nearby Seattle: One friend replied, "Young, suburban and low-key." Another friend replied, "Salmon, Pike's Market and Pearl Jam." When most people think of cities, they think of its qualities, traits, moods, special attractions and styles. They think about the experience of living there or visiting there. They might want to know if they can find jazz with soul, top performers and audiences that make the listening easy and pleasurable. They care less about the number of jazz clubs, art museums or parks than the quality of these features.

How about travel guides? Do they tell the true story? If we read about New York or Adelaide in a tourist booklet, will we uncover the real city?

With the possible exception of the Frank Sinatra question, most of the questions above could be asked about any city, . But the answers are rarely found in travel guides or encyclopedias.

Even if you visit a city like New York or Sydney physically, you may not come to know the "real city" very well, as most tourists taste only a small slice or sample of such cities. Mid town New York, with its hotels, theaters and restaurants catering to tourists, is a far cry from the Upper West Side with its multi ethnic populations and intriguing brownstones. Cross to the East Side through Central Park and one's impressions change once more, as brownstones give way to soaring apartment buildings that seem populated by folks who stride briskly with brief cases, cell phones and poodles. In Sydney, many tourists spend their time down at Circular Quay in an historical neighborhood called the Rocks. They wander past ferries and street performers on their way to the famed Opera House, all the while enjoying a diet of visual icons they may have tasted long before arriving in Australia. With just a few days to visit, they are unlikely to stray far from the beaten path.

It is difficult to build an understanding of a city, but it is easy to collect facts. How many museums? How many acres of park? How many people live in the city? What is the homicide rate? What are the icons? But even though understanding almost any complex aspect of human experience is difficult, the importance of knowing how to fashion a deep and comprehensive understanding is critical. If we or our students cannot do this kind of thinking, we become prisoners to the second hand smoke of propagandists, advertisers, promoters and marketeers. Without the skills to build and discover import, we may visit cities and simply end up taking the tour. We may spend our time in disneyfied neighborhoods that bear little resemblance to the original city. We see the city they want us to see. We buy a ticket and go for a ride. The city as theme park! Without the skills to build and discover import, we let doctors, politicians, insurance agents, politicians, morticians and pundits explain our world and our choices to us. We see the life they want us to see. We buy a ticket and go for a ride. Life as theme park! If we do not learn how to dig deeply, consider wisely and ponder the meaning of things, we are condemned to a kind of intellectual skating. We glide along the surface. We slide into MentalSoftness™ (see FNO, May, 2000, "Beyond Information Power.") We surrender. We give up the search for our own truths.

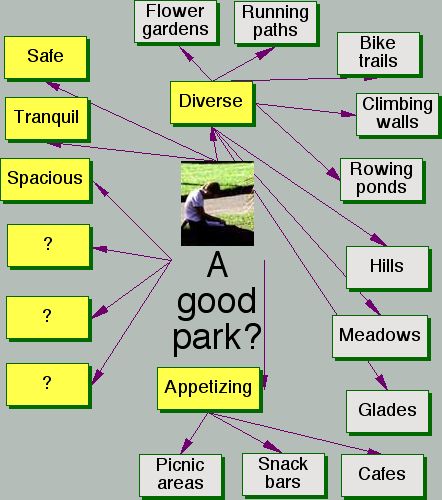

Who cares? Some times we ask students to do research that has little to do with verity. It may cast little light on the subject. It may not increase understanding or promote insight. It does not pass the test of "So what?" Collections of facts might not tell us much. How big are the parks? How many museums? How many people? Students may spend two weeks gathering information about a city or a country without coming to know the spirit and the character of that city or country at all. Knowing the number of museums is not the same as tasting them. Reading the crime rate across the city is not the same as strolling down its streets, noticing its street corner society, its homeless population, its workers and its families on the move. . Many of the other questions posed earlier in this article will take us beyond information to meaning . . . Does Sydney offer good parks? A good park? What does that mean? What are the traits or characteristics of a good park? How would I know a good park from this other side of the ocean?

Before we can judge the quality of New York's Central Park or Sydney's Botanical Gardens, we would have to define "goodness" when applied to parks. We ask our students to open a cluster diagramming program like Inspiration™ and have them map out the traits of a good park . . .

It turns out that knowing a city's character is a profoundly complicated task. Even those who live in a city may only know part of the city - their neighborhood and those aspects of the city they can appreciate through whatever filters they wear.

It turns out that just as "Beauty is in the eye of the beholder," determining the nature of a city is a personal judgment. One person hates Sydney but loves Melbourne. Another hates Melbourne but loves Sydney. The reasons for these feelings rarely have to do with the facts available about cities in encyclopedias. Virtual Social Studies We must guard against launching virtual social studies - the apparent study of other lands and cultures that amounts to little more than a glib and superficial dance through basic facts, stereotypes, icons, curios and misconceptions. Such studies may contribute little to the understanding of other lands - may actually distort the understanding of young people so that they come to see places like Australia as an extension of Outback Steak House or places like the United States as an extension of NYPD Blue. During a recent visit to a school district, I glanced through a social studies text that purported to introduce 6th grade students to regions and countries around the world. Because I have been fortunate to visit Australia and New Zealand 6-8 times each during the past three years, I was curious to see how this book might treat those countries. The treatment was superficial, thin and cursory. There simply wasn't enough space devoted to either country to do them justice. It was a gloss. The book shared some basic facts, made some geographical observations but ended up casting little light on either country. But textbooks are not the only problem. Many of the Internet sources used to study foreign lands are similarly shaped by tourism and entertainment values that rarely allow for exploration of deeper cultural or social issues. These sources rarely look on the darker side of these cultures. Crime? Drugs? The mistreatment of women? of indigenous peoples? Human rights and quality of life issues often fall into the shadows as we learn of great shopping, native foods and beachside villas. Social studies becomes a trek, a tour, an entertainment. What kind of city is LA? Do we visit Hollywood? Disney? The beach? Or do we look more carefully at the city and its issues? The sites of previous riots? The treatment of citizens by police? Is life getting better in LA? for whom? since when? What are people doing to make life better in LA? Which strategies have the most promise? How will California's power crisis change the lives of various types of citizens? How will skyrocketing electric bills influence small business people? big business? wealthy families? low income families? What would you do if you were mayor of LA? police commissioner? What should the American President do about California? (if anything) An Example of Learning for Understanding In an excellent program called "Looking At Ourselves and Others," Shallow, "entertainerized" learning about other countries or cities is indefensible. We create the illusion of learning, but the exploration is superficial and the outcomes untrustworthy. This approach does not sustain the kinds of analysis reflected in the following curriculum standards from Australian and American states:

Understanding by Exploring Deeply It is tempting to structure student learning so thoroughly that we leave little room for surprise, discovery and authentic idea building. A curriculum design model currently fashionable in the States (Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe, 1999) urges teachers to build curriculum units by identifying the essential questions and understandings envisioned by the curriculum standards in order to build backwards from these desired outcomes. If you know what you want students to know by the end of the unit - so the theory goes - then you can create a series of learning steps that will deliver the goods. While this strategy is appealing on the surface, it might lead to a kind of teacher structuring and control that actually deprives students of more authentic learning. In studying a city, for example, a teacher might have drawn five generalizations from the textbook:

On the surface, these kinds of understandings may seem standards-based.

But students must have a chance to wrestle with these kinds of issues in order to become thinkers. Some of the generalizations listed about New York above are highly questionable, but how likely is it that students will be given an opportunity to challenge or dispute the teacher's unit goals? In her chapter, "Using Technology to Enhance Student Inquiry," in the book reviewed in this issue, Technology in Its Place, Debi Abilock describes an approach to launching student investigations that is deep but practical:

Abilock's chapter provides an excellent model for launching authentic discovery that addresses the skills listed in state standards while putting the primary responsibility on students to create meaning. Teachers will find during these kinds of investigations that most members of the class (teacher included) will emerge with surprising new understandings that could not (and should not?) have been foreseen and pre-planned. While structure and scaffolding are attractive (See "Scaffolding for Success," FNO, December, 1999), we must be on guard against imposing our preconceptions (or the textbook's bias) on our students. We must leave room for surprise and discovery. Can we allow students to develop their own views of New York, Sydney, LA and Melbourne? Can we trust them to discover, to build and to generate fresh views of these cities? In next month's issue of From Now On, the lead article - "Building Good New Ideas" - will focus on the development of independent thinking and the fashioning of new ideas. References and Resources The Curly Flat - A web site devoted to Michael Leunig offering a brief biography, examples of his cartoons and merchandise. http://www.curlyflat.net/ Leunig Cards and Mugs - http://www.dynamoh.com.au/html/leunig_index.html |

Back to May CoverCredits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie. |

From Now On

From Now On