|

Enjoy Jamie McKenzie's book, Planning Good Change, by placing your order now. Click here to learn more. |

From Now On

From Now On

The Educational Technology Journal

Vol 9|No 10|June|2000

Making Good Change

Happen

Chapter One of Planning Good Change

To be released in January, 2001.

© 2000 Jamie McKenzie

about the author

Note: An earlier version of this chapter first appeared as an article in the March, 2000 issue of eSchool News.

It is easy to make change.

Change happens.

Even if we sit still . . . do nothing . . . change happens.

It is more difficult to make good change.

Change that makes life better. Change that endures.

Change that persists.

This book is about making good change by combining technologies with an emphasis upon literacy.

Making good change in schools is much more challenging than most policy makers and outsiders seem to understand.

We have decades of excellent research studies identifying which change strategies work and which fail. We have seen the folly of bandwagons and technological panaceas. We should have learned by now about making change that persists.

Been there.

Done that.

Sadly, much of the research on making good change has been widely ignored during the current rush to network schools.

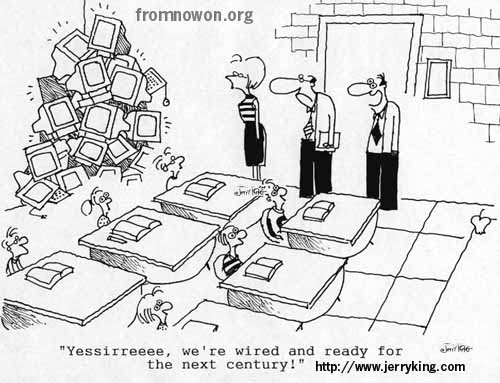

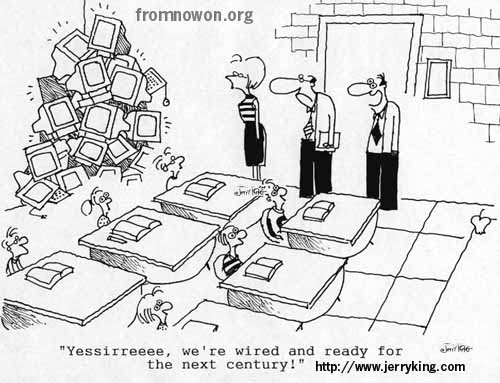

The scene that follows repeats itself all too often in places around the world as so many schools have been wired and equipped without careful thought.

When schools put the cart before the horse, spending most of their money on equipment and networking rather than professional development, program development, technical support and the “total cost of ownership,” (van Dam, 1999), they are likely to wake up with little to show for their hefty investment.

“Not much has changed.”

The superintendent and board president are wandering the halls of Millennium Elementary School with the principal. They are looking for signs that their investment in network technology has paid off.

In September, each classroom was equipped with three computers tied to the district network. Millennium is a wired school.

“And you say the teachers were expecting us?” the superintendent queries, disbelief creeping into her tone.

The principal has been around long enough to recognize more than disbelief in her voice.

“I told them not to launch anything out of the ordinary. I said that you would want to see a typical Wednesday afternoon.”

The superintendent stops walking and turns to face him directly.

“But, Don . . . we have walked into more than a dozen classrooms so far without seeing significant use."

"In two of the classrooms, we saw students doing drill and practice. In one room, we saw several students typing final drafts of papers from their handwritten work. In the other classrooms, we saw business as usual without anyone sitting near a computer. We saw no one using the Internet.”

The board president, a tall woman who usually wears a broad smile is now frowning.

“Yes, Don. I have to add my own sense of disappointment. I expected to see more powerful things by now. After all, it is March. They have had the computers for seven months. Why isn’t anybody using the Internet?”

Don Weatherby is not at all surprised by either woman’s reaction. For more than a year he has been arguing that more is needed than wires and computers. But the district has ignored his pleas for professional development and planning resources. The focus has been squarely on the equipment.

He shrugs. “Well,” he says, sounding proud rather than defensive, “Millennium has the best scores, the best teaching and the best community support of all the elementary schools in this district. These teachers will not do anything that might undermine that performance.”

“My staff is willing to integrate technology into the program only when they see how it can help them address the state curriculum standards and improve student performance, but they are quite reluctant to use technology for technology’s sake.”

“Change doesn’t happen in a school simply because you install new equipment,” he continues, his tone quite serious now.

Don Weatherby was not sure whether his superintendent or the board president would have anything nice to say about him as they drove away from Millennium that afternoon in the superintendent’s red SUV, but he was determined to go on speaking his mind.

As the district rushed to network schools and classrooms, he had often felt like the boy in the Hans Christian Andersen story who points out that the Emperor has no clothes.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Lopsided Planning Leads to Disappointments

Armed with visionary statements and promises from politicians and business folks intent on creating a “knowledge economy,” we have committed a fortune to a venture severely flawed by its lopsided focus on equipment and connectivity rather than learning. What we have failed to do is demonstrate a connection between all of this new equipment and the outcomes for which schools, teachers and principals are now rewarded (or punished).

Evidence is accumulating from early studies that the billions of technology dollars spent each year for the past 3-4 years have had minimal impact on the daily practice of teachers across the land and scant impact on how students spend their time in schools.

Education Week’s Technology Counts’99 reported that networking of schools is proceeding at a rapid pace and Internet access to classrooms is much greater now than several years ago, but teacher use remains disappointing:

- . . . a new Education Week survey has found that the typical teacher still mostly dabbles in digital content, using it as an optional ingredient to the meat and potatoes of instruction.

- Almost two-thirds of teachers say they rely on software or Web sites for instruction “to a minimal extent” or “not at all.”

- Trotter, Andrew. “Preparing Teachers For the Digital Age.” Technology Counts ’99. Education Week, 1999.

- September 23, 1999.

http://www.edweek.org/sreports/tc99/articles/teach.htm

This lack of impact should come as no surprise to those who have taken the time to learn from our past mistakes. When Sputnik caused a panic four decades back, the fear of falling behind the Russians provoked a hemorrhage of federal funds to revolutionize the ways that schools taught math, science and just about everything.

The results of all this funding? There were many failures and some successes but a general frustration with the challenge of transferring, transporting and transplanting changes from one system to another.

Educators do have a history of trying to make change, but it is rarely read or heeded by bandwagon promoters. The consequences can be severe.

- Those who cannot remember the past

- are condemned to repeat it.

- George Santayana

Chapter Eight of this book, “Beware the Shallow Waters: The Dangers of Ignoring the History and the Research on Change in Schools,” presents a more detailed review of this literature on change,

In this introductory chapter I will briefly mention several bold stroke approaches to change that have been rarely heeded by those busily networking schools. Succeeding chapters will expand upon these strategies and others to provide the reader with a way of looking at and managing this planning process with skill and judgment.

Basic Principles to Guide Change Efforts

1. Making good change requires a focus on a purpose likely to win broad acceptance.

Without the enthusiastic endorsement of the teachers in a building, not much change is likely to occur. To win this endorsement, the innovation being proposed must promise outcomes and benefits that match the daily realities, concerns and desires of the staff.

Teachers have seen bandwagons come and go. They are appropriately skeptical about untested, expensive changes that seem peripheral rather than central to their purpose. They want to know how this venture will improve student performance.

In the case of educational technologies, there is often a vacuum when it comes to educational purpose. We too often network because it is “the thing to do.” Teachers usually look askance at such efforts.

2. Making good change demands the cultivation and engagement of the key stakeholders within the school community, especially the classroom teachers.

The decision to network a school is usually made by powerful figures outside the school. Failure to involve building staff in the development of the learning program, the design and placement of the network resources and a robust 3-4 year professional development program is courting disaster.

3. Making good change involves a strategic and balanced deployment of resources.

Schools optimize use by moving resources around to where they will do the most good. They also define resources broadly to provide a balance between the human and technical aspects of the initiative, allocating 25 per cent or more of their budget to professional development and a substantial salary budget to fund technical support in order to avoid the “Network Starvation” outlined in Chapter Nine.

4. Making good change necessitates time away from the “daily press” of teaching.

Michael Fullan claims the “daily press is a major obstacle to making changes in classroom practice, as the drive to maintain forward progress often precludes an investment in sideways explorations and innovation.” If districts expect to see broad-based adoption of new technologies, they must provide 30-60 hours yearly for teachers to meet, to learn and to invent classroom units.

Good Change is Possible

This book is designed to offer hope and inspiration as well as skill and method to those who feel passionately about changing schools for the better. Many schools already possess many of the key elements required to make smart use of the new tools. Other have much cultivating to do. But regardless of the starting point, all schools can make dramatic progress toward the goal of becoming information literate communities. All schools can realistically expect to equip students with the kinds of strong questioning and thinking skills that will serve them well as they find their way into this new century.

Save 20% on Jamie McKenzie's next book, Planning Good Change, by placing your order now. Click here to learn more.

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.

|

|

It is easy to make change.

Change happens.

Even if we sit still . . . do nothing . . . change happens.

It is more difficult to make good change.

Change that makes life better. Change that endures.

Change that persists.

This book is about making good change by combining technologies with an emphasis upon literacy.

Making good change in schools is much more challenging than most policy makers and outsiders seem to understand.

We have decades of excellent research studies identifying which change strategies work and which fail. We have seen the folly of bandwagons and technological panaceas. We should have learned by now about making change that persists.

Been there.

Done that.

Sadly, much of the research on making good change has been widely ignored during the current rush to network schools.

The scene that follows repeats itself all too often in places around the world as so many schools have been wired and equipped without careful thought.

|

When schools put the cart before the horse, spending most of their money on equipment and networking rather than professional development, program development, technical support and the “total cost of ownership,” (van Dam, 1999), they are likely to wake up with little to show for their hefty investment. |

|

“Not much has changed.”

The superintendent and board president are wandering the halls of Millennium Elementary School with the principal. They are looking for signs that their investment in network technology has paid off.

In September, each classroom was equipped with three computers tied to the district network. Millennium is a wired school.

“And you say the teachers were expecting us?” the superintendent queries, disbelief creeping into her tone.

The principal has been around long enough to recognize more than disbelief in her voice.

“I told them not to launch anything out of the ordinary. I said that you would want to see a typical Wednesday afternoon.”

The superintendent stops walking and turns to face him directly.

|

“But, Don . . . we have walked into more than a dozen classrooms so far without seeing significant use." |

|

"In two of the classrooms, we saw students doing drill and practice. In one room, we saw several students typing final drafts of papers from their handwritten work. In the other classrooms, we saw business as usual without anyone sitting near a computer. We saw no one using the Internet.”

The board president, a tall woman who usually wears a broad smile is now frowning.

“Yes, Don. I have to add my own sense of disappointment. I expected to see more powerful things by now. After all, it is March. They have had the computers for seven months. Why isn’t anybody using the Internet?”

Don Weatherby is not at all surprised by either woman’s reaction. For more than a year he has been arguing that more is needed than wires and computers. But the district has ignored his pleas for professional development and planning resources. The focus has been squarely on the equipment.

He shrugs. “Well,” he says, sounding proud rather than defensive, “Millennium has the best scores, the best teaching and the best community support of all the elementary schools in this district. These teachers will not do anything that might undermine that performance.”

“My staff is willing to integrate technology into the program only when they see how it can help them address the state curriculum standards and improve student performance, but they are quite reluctant to use technology for technology’s sake.”

“Change doesn’t happen in a school simply because you install new equipment,” he continues, his tone quite serious now.

Don Weatherby was not sure whether his superintendent or the board president would have anything nice to say about him as they drove away from Millennium that afternoon in the superintendent’s red SUV, but he was determined to go on speaking his mind.

As the district rushed to network schools and classrooms, he had often felt like the boy in the Hans Christian Andersen story who points out that the Emperor has no clothes.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Lopsided Planning Leads to Disappointments

Armed with visionary statements and promises from politicians and business folks intent on creating a “knowledge economy,” we have committed a fortune to a venture severely flawed by its lopsided focus on equipment and connectivity rather than learning. What we have failed to do is demonstrate a connection between all of this new equipment and the outcomes for which schools, teachers and principals are now rewarded (or punished).

Evidence is accumulating from early studies that the billions of technology dollars spent each year for the past 3-4 years have had minimal impact on the daily practice of teachers across the land and scant impact on how students spend their time in schools.

Education Week’s Technology Counts’99 reported that networking of schools is proceeding at a rapid pace and Internet access to classrooms is much greater now than several years ago, but teacher use remains disappointing:

- . . . a new Education Week survey has found that the typical teacher still mostly dabbles in digital content, using it as an optional ingredient to the meat and potatoes of instruction.

- Almost two-thirds of teachers say they rely on software or Web sites for instruction “to a minimal extent” or “not at all.”

- Trotter, Andrew. “Preparing Teachers For the Digital Age.” Technology Counts ’99. Education Week, 1999.

- September 23, 1999.

http://www.edweek.org/sreports/tc99/articles/teach.htm - Almost two-thirds of teachers say they rely on software or Web sites for instruction “to a minimal extent” or “not at all.”

This lack of impact should come as no surprise to those who have taken the time to learn from our past mistakes. When Sputnik caused a panic four decades back, the fear of falling behind the Russians provoked a hemorrhage of federal funds to revolutionize the ways that schools taught math, science and just about everything.

The results of all this funding? There were many failures and some successes but a general frustration with the challenge of transferring, transporting and transplanting changes from one system to another.

Educators do have a history of trying to make change, but it is rarely read or heeded by bandwagon promoters. The consequences can be severe.

- Those who cannot remember the past

- are condemned to repeat it.

- George Santayana

- are condemned to repeat it.

Chapter Eight of this book, “Beware the Shallow Waters: The Dangers of Ignoring the History and the Research on Change in Schools,” presents a more detailed review of this literature on change,

In this introductory chapter I will briefly mention several bold stroke approaches to change that have been rarely heeded by those busily networking schools. Succeeding chapters will expand upon these strategies and others to provide the reader with a way of looking at and managing this planning process with skill and judgment.

Basic Principles to Guide Change Efforts

1. Making good change requires a focus on a purpose likely to win broad acceptance.

Without the enthusiastic endorsement of the teachers in a building, not much change is likely to occur. To win this endorsement, the innovation being proposed must promise outcomes and benefits that match the daily realities, concerns and desires of the staff.

Teachers have seen bandwagons come and go. They are appropriately skeptical about untested, expensive changes that seem peripheral rather than central to their purpose. They want to know how this venture will improve student performance.

In the case of educational technologies, there is often a vacuum when it comes to educational purpose. We too often network because it is “the thing to do.” Teachers usually look askance at such efforts.

2. Making good change demands the cultivation and engagement of the key stakeholders within the school community, especially the classroom teachers.

The decision to network a school is usually made by powerful figures outside the school. Failure to involve building staff in the development of the learning program, the design and placement of the network resources and a robust 3-4 year professional development program is courting disaster.

3. Making good change involves a strategic and balanced deployment of resources.

Schools optimize use by moving resources around to where they will do the most good. They also define resources broadly to provide a balance between the human and technical aspects of the initiative, allocating 25 per cent or more of their budget to professional development and a substantial salary budget to fund technical support in order to avoid the “Network Starvation” outlined in Chapter Nine.

4. Making good change necessitates time away from the “daily press” of teaching.

Michael Fullan claims the “daily press is a major obstacle to making changes in classroom practice, as the drive to maintain forward progress often precludes an investment in sideways explorations and innovation.” If districts expect to see broad-based adoption of new technologies, they must provide 30-60 hours yearly for teachers to meet, to learn and to invent classroom units.

Good Change is Possible

This book is designed to offer hope and inspiration as well as skill and method to those who feel passionately about changing schools for the better. Many schools already possess many of the key elements required to make smart use of the new tools. Other have much cultivating to do. But regardless of the starting point, all schools can make dramatic progress toward the goal of becoming information literate communities. All schools can realistically expect to equip students with the kinds of strong questioning and thinking skills that will serve them well as they find their way into this new century.

Save 20% on Jamie McKenzie's next book, Planning Good Change, by placing your order now. Click here to learn more.

Credits: The photographs were shot by Jamie McKenzie.

Copyright Policy: Materials published in From Now On may be duplicated in hard copy format if unchanged in format and content for educational, nonprofit school district and university use only and may also be sent from person to person by e-mail. This copyright statement must be included. All other uses, transmissions and duplications are prohibited unless permission is granted expressly. Showing these pages remotely through frames is not permitted.

FNO is applying for formal copyright registration for articles.